Towards a Capasity Development Framework - For Land Policy in AfricaSolomon HAILE, Ombretta TEMPRA, Remy SIETCHPING, UN-Habitat, Kenya

1) The article discusses the Land Policy Initiative (LPI) and how relevant activities are planned and implemented to think through and develop strategies and road maps that will culminate into the development of a coherent, unified and cutting edge Capacity Development Framework (CDF). LPI Capacity Development was a sub theme at the Working Week 2013. The LPI was discussed at the GLTN/Director General forum which were spread over 4 sessions during the Working Week and furthermore there was a special session on Africa LPI Capacity Development where Solomon Haile presented the proposed Africa LPI Capacity Development initiative. ABSTRACTCapacity development is at the heart of the Land Policy Initiative

(LPI). The AU Declaration on Land Issues and Challenges in Africa urges

member states to “build adequate human, financial, technical capacities

to support land policy development and implementation.” Drawing on the

overarching guidance provided in the Declaration, the LPI Strategic Plan

and Roadmap provides impetus for action by making capacity development

one of its key objectives and aiming at “facilitating capacity

development and technical assistance at all levels in support of land

policy development and implementation in Africa.” Capacity development

also features in other strategic objectives of the LPI Strategic Plan

and Roadmap. Knowledge creation/documentation/dissemination as well as

advocacy and communication, which form other elements of the Strategic

Plan and Roadmap, have significant capacity development overtones. 1. BACKGROUND

|

|

|

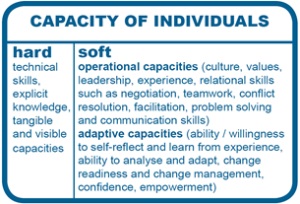

Figure1. Schematic Representation of Individual Capacities4) and Organizations’ Capacities5)

In an effort to clarify the nature of capacity development in the LPI context, there a number of principles that have been specified in the Background Paper as well as draft CDF. These include the following:

In the process of refining the outline and the drafting of the

CDF, this was one of the questions that has repeatedly been raised

and responded to in many different ways. The one answer that came up

quite frequently during engagements with stakeholders is the need to

have a unified and comprehensive approach wherein shared principles,

methodologies, roles and responsibilities are to be clearly spelled

out. It is argued that such a framework will make the goals and

methodologies of developing capacities for land policy processes

across Africa a shared agenda in much the same way land stakeholders

in Africa are making the F&G and the Declaration on Land Issues and

Challenges a common strategic frameworks and joint reference points

to get the most out of limited resources. The CDF for Land Policy in

Africa aims to provide strategic and workable guidance to African

member states and other African land sector stakeholders in the

design, implementation and progress tracking of land policies at

continental, regional and national / local levels. The guidance will

include identifying and working on common capacity development

themes, processes, principles, approaches, etc that may be needed to

meet country or region specific requirements.

Like the F&G, the CDF will not impose a one-size-fits-all type of

capacity development approaches, principles and activities. The

diversity of existing capacities and the differences in capacity

needs at different levels across the continent are well recognized

and do not allow top-down program design and delivery. Still, there

are opportunities, challenges and risks that regions and countries

in Africa share with one another which lend themselves to a

well-designed comprehensive and unified framework. Finally, if one

considers the bigger picture, it is easy to note that this quest for

a common and unified framework is also part and parcel of the bigger

continental political agenda which aspires to bring people and

nations together through harmonization of policies, development of

supra-national infrastructure, promotion of trade and investment,

etc.

If data about land and associated capacity land interventions in Africa were carefully assembled and analyzed, it would be clear for all to see the extent to which these interventions are piecemeal and uncoordinated contributing to the duplication of activities and misuse of precious human and financial resources, The Framework therefore intends to facilitate coordination between and among stakeholders with a view to minimizing duplication and maximizing efficiency. By promoting peer-to-peer exchange, Africans with a unified and shared capacity development vision can learn from and build on each other strengths. On the strength of this coordination, Africans and their development partners can expect to get better value for money. Also, the Framework anticipates facilitating a mechanism whereby novel thinking and innovations in capacity development can easily be identified, adapted and used across Africa.

In addition to a lack of well thought-through land policies,

there are certain land issues that have emerged as key priorities of

most stakeholders in Africa. These are issues that stand in the

critical path of realizing the land resources potential of the

continent for poverty reduction and economic growth. Addressing

these issues within the framework of land policies (please note that

land policies are political instruments that can help bring about

comprehensive and meaningful reform) could jumpstart dysfunctional

land systems in many parts of Africa. This is thus one of the

rationales why the LPI needs a comprehensive and unified CDF. During

the preparation of the F&G for Land Policy in Africa, the Land

Policy Initiative (LPI) conducted five regional assessments – one

for each African region – through the Regional Economic Communities

(RECs). These included undertaking research, facilitating extensive

consultations and conducting validation workshops. It is through

these and similar engagements that the LPI has realized that some of

the priority issues that need to be mainstreamed in Africa’s land

policy thinking include women’s land rights, large scale land

based investment, land administration, land conflicts, customary

tenure and urban and peri-urban land issues.

In sum, it can be said that there is much value that can be added to

the land policy processes in Africa through a comprehensive

continental framework. The draft CDF succinctly outlines the

benefits like this: “A comprehensive approach would principally

entail a departure from the isolated, piecemeal approaches that have

characterized preceding efforts to develop capacities. Fragmented

approaches are often output-oriented rather than result-oriented. A

unified, comprehensive capacity development framework for land

policy that focuses on results has the potential to contribute to

sustainable land policies, as well as their implementation and

monitoring, by harnessing economies of scale….. A unified approach

also engenders coherence and synergy between the various activities

or countries involved. Such coherence is achieved through ongoing

exchange and feedback between participating entities, plugging the

gaps between technical and non-technical, rural and urban, or

stakeholders in development sectors. Finally, economies of scale are

realized through increased efficiencies (reduced transaction costs)

that result from a coordinated approach.”

The ‘how’ question of capacity development for land policy has

two dimensions: methodology and substance on the one hand and modus

operandi on the other hand. The latter refers to how different

stakeholders are to be engaged and assisted to contribute to the

attainment of required capacities in a specific context. It includes

things like working with and through partners. In relation to

training, for example, identifying and working with regional

learning centers is an important strategy. This entails supporting

selected training centers to grow in to “centers of excellence” in

regard to land policy processes. And they will then become focal

points for training in their respective regions including for

replicating training rolled out at continental level and expanding

outreach. On the methodology front, some of the things that are

being considered include action learning, needs assessment, good

practice training, etc and the way these link up with priority

matters like women land rights, customary tenure for example. Also,

the CDF is likely to move land stakeholders in Africa away from

training-only capacity development to the one that promotes

diversified approaches and tools (training plus or more than

training). The other capacity development approaches being

suggested include technical assistance, peer-to-peer exchange,

coaching and mentoring, experiential learning, and exposure visits.

Overall, there are very many different ways whereby capacities for

land policy processes can be developed. A strategic choice has to be

made based on 1) cutting edge thinking in the field 2) the needs of

the continent and its constituent parts 3) the innate requirements

of land policy processes. To illustrate, one may for example say

that capacity development for land policy should accentuate strong

sensitization and awareness raising exercises that enhance the

understanding of issues among policy makers and the formation of

social movements at the grassroots. Likewise, it can be said that

capacity development for land policy development should enhance

multi-disciplinary analysis, effective integration and harmonization

of the various facets of land (spatial, legal, economic, social,

cultural, and political). For land policy implementation, all that

capacity development needs to do is to strengthen organizations and

agencies, be they state, quasi-state, local, community or private.

These are all good and correct. But, such generic prescriptions will

not go far enough especially when dealing with complex capacity

development issues. Solving complex capacity issues and achieving

results require inclusive process, nuanced analysis and tools (‘how

to’ methods) that precisely determine what needs to be done and how

it should be done. This again brings to the fore the how question?

How are capacities to be developed? Engagements with the CDF

stakeholders have shown that capacities for land policies are to be

developed through:

Of the many principles outlined in section 3, demand-driven capacity development figures out prominently. Assessing needs or gauging demand indeed is of utmost significance, for it allows overcoming many of the failings of conventional capacity development. In the context of land policy process, this doesn’t mean sitting and waiting for the requests to come from various stakeholders. It rather means going to the field (literally or virtually), working with relevant actors to determine what needs to be done and how to make land policy process move forward. A capacity development that is anchored in strong needs assessment is the basis for developing home-grown and country owned programs. It is also the starting point to clarify SMART goals and achieve results. Needs assessment is therefore one of the tools that inform how capacity development for land policy processes must be designed and implemented. Not only is this thinking embedded in the emerging CDF, but also it is being taken further by analyzing good practices that make needs assessment work better for land policy processes in Africa. The quality of the capacity needs assessment has clearly direct implications in the quality, and therefore the outcome, of capacity development programmes. Specific areas of capacity need should always be assessed – whenever possible through participatory processes - within the framework of larger system-wide capacities with a view to contributing to higher level goals that underpin systemic, transformative and sustainable changes. Good practice in capacity needs assessment6) has the following attributes:

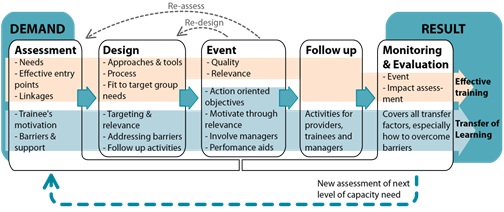

Increasing awareness of the limitations of conventional training

and of the fact that developing capacity in complex systems requires

a long-term strategic approach within which shorter initiatives can

be framed as stepping stones to longer term strategic goals. In line

with this thinking and drawing on UN-Habitat experience in training

and capacity development, an improved approach to training has

emerged. The capacity development strategy developed by the GLTN to

specifically address capacity gaps in the land sector says:

“Whether short or long-term in nature, all capacity development

initiatives work best if they are viewed as a process, not an event.

Such processes will always comprise some key components, namely:

assessment, design, the two parts of the delivery phase (event and

follow-up), and monitoring and evaluation, with iterative feedback

loops and impact assessment incorporated at a number of points (…)”.7)

The components of good practice training are:

Figure 2. The Good Practice Training Cycle

Source: UN-Habitat Good Practice Note on Training

Formal education is arguably one of the most important ways of

developing capacities for the land sector. It includes education

programmes and institutions that provide training and capacity

development at certificate, diploma, under-graduate and

post-graduate degree levels. A capacity needs assessment for land

surveyors carried out in Francophone Africa8)

captured some of the gaps and needs for improvement in the education

of surveyors in the region. Similar findings came out of another

research entitled ‘Human9)

Capacity Needs Assessment and Training Program Development for the

Land Sector in in Kenya’.10)

In summary, it can be said that a large number of technical

education programmes in Africa are old fashioned, structured around

colonial models more fit to respond to the land sector needs of 20th

century Europe rather than the 21st century fast-changing and

rapidly urbanizing Africa.

Too few technical schools train small numbers of professionals at

high cost. This is one of the reasons for the ongoing shortage of

key professionals apart from being unsustainable. The knowledge

imparted often focuses on ‘hard’ skills only, while much needed

‘soft’ skills are neglected. It serves more the interest of

conventional land administration practices that have proven to be

too rigid and costly to service contemporary Africa. As a

consequence, this produces professionals who are poorly equipped to

face the reality of land challenges, but to entrench outdated,

expensive and elitist thinking. It hardly empowers to be creative

and devise affordable, flexible, pro-poor, gender responsive and

context specific home-grown land administration solutions.

There is therefore a need for a more innovative approach to capacity

development in the technical disciplines of the land profession.

Africa needs to have a larger pool of land professionals with

different levels of skills that can better respond to challenges on

the ground. It needs professionals whose knowledge and skills sets

meet requirements of its people. This does not always mean highly

trained university graduates. In some contexts, this could mean

creating a large cadre of paralegals and ‘barefoot’ surveyors. In

other contexts, this could mean people with specialized knowledge of

conveyancing, valuation, etc. A great deal of capacity issues in

many land offices could be met through technical and vocational

education and training. The CDF needs to inculcate this kind of mind

sets through its engagements with land training providers. Also, the

capacity of land practitioners, such as traditional and informal

land managers, community and grassroots members, should be

developed. New land administration tools, techniques and

technologies have to be incorporated into the learning processes.

The approach the CDF is likely to espouse will aim to change the way

land training is delivered on the continent and hope to “catch” the

future leaders and land professionals “young”, i.e. before

conventional systems corrupt their minds.

In Africa, as is the case elsewhere in the world, the diversity

of land sector actors is immense and each represents different

roles, interests, capabilities and motivations. Each actor can

assume different roles at the different stages of land policy

processes (e.g. development, implementation, and monitoring).

This section broadly outlines the roles that different land and

non-land actors play in capacity development. The words ’broad

outline’ are key because the actors and stakeholders and the roles

with which they identify are context-specific. And these contexts

are too many and in some cases too specific to list and summarize

here. Each land sector stakeholder has multiple roles to play in

capacity development for land policy in Africa. These roles can be

referred to as capacity development beneficiary, capacity

development provider, and capacity development broker, but it is

important to keep in mind that most stakeholders have more than one

type of role. Also, it is important to note that each stakeholder

has and needs different types of capacities for different stages of

land policy (development, implementation, and progress tracking). To

breakdown and simplify a complex array of actors and roles, one of

the analytical frameworks being considered and used to map partners

and stakeholders, roles and responsibilities, etc is the following:

The above framework, seemingly simple and straightforward, can become complicated when a specific agenda that is relevant for a particular context is identified and stakeholders want to action it. Still, there are tools to analyze who does what. For the purpose of this paper, the most important thing to note is that identifying roles and responsibilities of various actors is as important as having cutting edge tools and methodologies.

The paper has thus far tried to shed some light on issues and

themes underpinning the capacity development thinking within the LPI

framework. It has also highlighted the direction that the emerging

CDF is taking. The draft CDF is still very much a work in progress.

Therefore, it has not been possible to fully share what is in the

draft CDF. However, the material that has been presented in this

paper is more than adequate to share information, to solicit views

and feedback that will strengthen the CDF, and thereby help all

those interested in the agenda to contribute to the LPI vision,

mission and mandate.

As a way forward, it may be useful to take up a couple of themes

which the paper has alluded to, but has not fairly well dwelt on.

The first is partnership. Developing the capacity of African land

sector stakeholders to implement the Declaration on Land Issues and

Challenges in Africa and the F&G on Land Policy is a goal that

requires the joint effort of a large number of partners. The draft

CDF recognizes that a well-structured collaboration based on shared

values, complementarity, comparative advantage, is vitally important

and must be actively sought, strengthened and expanded. The CDF will

promote this and it is hoped that relevant actors on the continent

will embrace the CDF to leverage capacity development resources to

create low-cost, high-value programs. The collaboration can include

harmonizing and integrating capacity development opportunities

offered by existing initiatives, programs, institutions and

platforms. Obviously, such collaboration can only enhance coherence

among various initiatives and the relevance and credibility of all

those involved. Linkages among different land initiatives, including

capacity development activities is in the best interest of all

actors as it enables them to avoid conflicting messages and overlaps

and waste in scarce financial and human resources. The CDF can, when

completed, be a platform that provides opportunities to promote the

coming together of all actors to maximize relevance and results. The

extent to which partners will be committed to work together under

the emerging CDF will determine whether or not these goals will be

achieved.

The second is about resources. Africa counts on a range of partners

to support the implementation of the CDF. Continental and regional

bodies, national and local authorities, national and international

NGOs, training and research institutions, traditional leaders,

community-based organizations, professional associations, private

sector, and bilateral and multilateral development partners have all

an important role to play and are called upon to embrace the LPI and

its CDF in this spirit.

Land policy development is a lengthy process. It is therefore not

cheap. As well, it should not be done ‘on the cheap’ especially if

this means compromising inclusiveness and consultative processes.

Land policy implementation is even more costly. These costs should

be assessed well in advance in the policy reform and design stage.

The same could be said about capacity development for land policy.

Resources to jumpstart and sustain it should be estimated and

catered for early in the process to ensure a degree of preparedness

and prevent capacity constraints from standing in the way of policy

development and implementation. In regard to resource allocation,

international development partners have a significant role to play.

But, external funding alone cannot and should not fully cater for

this. African governments should be prepared to be a primary source

of funding and finance land policy processes and the attendant

capacity development activities.

2) The paper draws from the CDF Background Paper and the draft

CDF. These are duly acknowledged where appropriate.

3) OECD (2006), “The Challenge of Capacity Development: Working

Towards Good Practice”, DAC Guidelines and Reference Series, OECD,

Paris. http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/4/36/36326495.pdf

4)Schematic representation reflecting the Core Concept section of

the LenCD Learning Package for Capacity Development, available at

www.lencd.org/group/learning-package

5) Schematic representation re-elaborated from the conceptual and

operational frameworks for institutional capacity development

developed by the UN-Habitat Training and Capacity Building Branch

(update / check / improve reference)

6) ‘UN-Habitat Good Practice Note: Training’, page 19

7) GLTN Capacity Development Strategy, draft document, June 2012,

following from e.g. OECD (2006). The Challenge of Capacity

Development: Working Towards Good Practice. OECD Publishing: Paris,

France. OECD (2006), “The Challenge of Capacity Development: Working

Towards Good Practice”, DAC Guidelines and Reference Series, OECD,

Paris.

http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/4/36/36326495.pdf

8) 'Séminaire d’évaluation des besoins en formation des géomètres en

Afrique subsaharienne’, 2012

9) The term human capacity is used in this assessment to make a

distinction between what people in organizations require and what

those organizations require in terms of hardware, facilities, etc.

10) Unpublished Report on ‘Human Capacity Development Needs

Assessment and Training Programme for the Land Sector in Kenya’ .

Solomon Haile, Ph.D

Global Land Tool Network

Urban Legislation, Land and Governance Branch, UN-Habitat

P.O.Box 30030-00100

Nairobi, KENYA

Tel:+254207625152

E-mail:

Solomon.Haile@unhabitat.org

Ombretta Tempra

E-mail:

Ombretta.Tempra@unhabitat.org

Remy Sietchiping, PhD

United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat)

P.O. Box 30030

Nairobi 00100, KENYA

E-mail:

Remy.Sietchiping@unhabitat.org