Article of the Month - April 2022 |

|

| Charisse Griffith-Charles |

This article in .pdf-format (18 pages)

The aim of this article is to explore the individual indicators such as the LANDex with a focus on gender disparities in land tenure. Sample sets extracted from Sain Lucia's land registration database were used to exaine whether gender disparity occurs in land tenure and if so, to what extent it occurs.

Gender disparity in land tenure is not perceived to be a significant

issue in the Caribbean. However, global indicators usually require some

focus on gender data even though this is not gathered or tracked as a

priority in the region. These standardised global indicators are useful

to benchmark land administration systems one against the other in order

to monitor progress and development, or to evaluate systems for

attainment of specific goals. The Global Land Governance Index or LANDex

is a group of indicators promoted by the International Land Coalition

(ILC) that can be used for benchmarking in this way as well as for

evaluation of countries’ achievements toward the Sustainable Development

Goals (SDGs). The aim of this work was to explore the individual

indicators such as the LANDex with a focus on gender disparities in land

tenure. Sample sets extracted from Saint Lucia’s land registration

database were used to examine whether gender disparity occurs in land

tenure and if so, to what extent it occurs.

Results from the case study indicated that gender disparity in land

tenure does exist to the extent where individual female land owners

owned less than fifty percent of the number of parcels of land that

individual male land owners held. It was noted that the statistic

did not account for scale and culture differences and considerable

additional information was required to fully elaborate on the statistic

as it provided only limited information on the complex situation.

The findings were significant for identifying where these disparities

occurred so that the issue can be placed on the agenda of many Caribbean

countries.

Gender and tenure issues are inextricably linked internationally and result in inequity in rights that impact societies. Gender disparity in land tenure is not perceived to be a problem in the Caribbean (Griffith-Charles 2004) as women hold a relatively high level of empowerment in education, labour, and political spheres. The World Economic Forum (Crotti et al. 2020) publishes an annual report on gender gaps in countries of the world. In 2020, The Bahamas was ranked sixth in the world with Trinidad and Tobago at twenty-fourth and Barbados at twenty-eighth place. As a result of this attitude, gender is not always tracked to support or contradict this perception. There is a need, however, to demonstrate whether or not there is gender disparity specifically in land tenure so that interventions aimed at development may be channelled appropriately for the benefit of the Caribbean societies and so that the incidence may be benchmarked against other societies. This paper looks at existing sparse data in a small statistical sample of land ownership in a case study in Saint Lucia and makes suggestions for addressing this land information issue.

Gender imbalance in land rights can affect livelihoods and food security. Gender in land in Latin America is discussed by Deere and León (2003) who indicate that there may be several reasons for a disparity to exist including culture, religion, and tradition as practised in inheritance, marriage and social processes and relationships. The disparity itself does not tell the entire story and addressing the disparity to provide equality may require actions that affect practices in society leading to loss of deeply held cultural traditions. Acquiring land by inheritance, for example, may follow patrilineal customs even though state laws may provide for equality of treatment. At the state administrative level, addressing disparities may also mean amending or introducing policies, legislation and institutions for taking action.

Gender information is now required by aid agencies, not only for establishing and monitoring whether good governance guidelines as outlined in frameworks such as the Land Governance Assessment Framework (LGAF) (Deininger, Selod, and Burns 2011) or the Voluntary Guidelines on Responsible Governance of Tenure (VGGT) (FAO. 2014) are being followed, but also for reporting on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as most countries have committed to so doing. It has been identified that several of the SDGs have direct links to land and land tenure. Specifically, the Global Land Tool Network (GLTN) has identified that SDGs 1, 2, 5, 11, and 15 and their sub-components of 8 targets and 12 indicators, relate directly to land. Gender imbalances in these specific components may therefore impact the abilities of states to reduce poverty, which is the focus of the SDGs. This fact is not globally recognised. The Trinidad and Tobago Voluntary National Report (Government of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago 2020), for example, while including a discussion on gender disparity, does not include the relationship of gender disparity to land and development and thus the reduction of poverty that can be effected by interventions in land tenure.

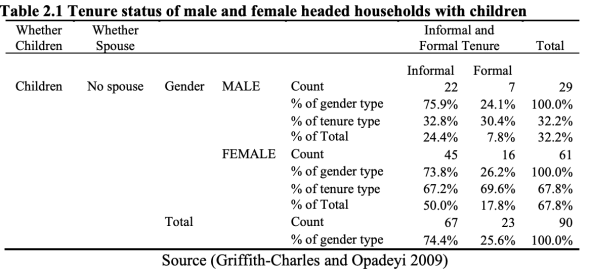

A study done as a forerunner for implementing adjudication and titling in Trinidad and Tobago indicated that female land owners were a vulnerable group in the pending registration project as a purposive sampling of informal occupation on state land produced a statistic that 73% of the female headed households polled were in informal occupation (Griffith-Charles and Opadeyi 2009). Table 2.1 shows the details of the statistic as it presents the breakdown of percentages within female and male headed single parent households with children who reside on formal and informal land within the specific sampled areas. It also shows that 67% of the informal parcels are occupied by female headed households as opposed to 33% for male headed households. It can also mean that interventions should target female headed households primarily to reach more families and children in poverty. The land registration process could put them at a disadvantage if power relations meant that they could not advance and demand their land rights. It is not perceived that there are restrictions to women holding land in Trinidad and Tobago as legislation over the years have sought to address historical inequities. For example, the Cohabitational Relationship Act No. 30 of 1998 (Republic of Trinidad and Tobago 1998) and the Distribution of Estates Act No. 28 of 2000 (Republic of Trinidad and Tobago 2000) provided for women who were in cohabitational relationships and their offspring from being displaced from the home on the death of their partners. It was only in 1975 with the Married Persons Act of 1975 (Republic of Trinidad and Tobago 1976) that married women were allowed personal property that could be disposed of by them alone (Wylie 2011).

While the Land Settlement Agency (LSA), which is the institution that manages informal settlements on state land in Trinidad and Tobago, encourages women to apply for the land they occupy informally, the inequity is usually an indirect result of other factors such as child rearing, which reduces the ability to work and to save money for land purchase for single parents, who are generally female. As quoted in a study directed at perceptions of tenure security in informal communities in Trinidad and Tobago (Griffith-Charles 2004, 106), when asked whether there was gender equality for women in land issues a male respondent stated:

“Equal! Even a little better. Whereas people will help women you think anybody would come and help me?”

Although this one quote gives anecdotal evidence of a perception that women have certain privileges, more rigorous data gathering would be required to determine the status.

Information on land tenure in relation to gender is somewhat sparse for the Caribbean. This paper uses existing data and publications related to perceptions surrounding gender and land in a more qualitative than quantitative assessment of the situation. A small study on Saint Lucia’s land registry data gives some support to a central idea on the status of gender and land tenure in the Caribbean. For this work, the registry data was extracted for a sample area of parcels in an urban/peri-urban and primarily residential area of Saint Lucia called Babboneau. Since gender was not an attribute noted on the data in the land registry, assumptions were made about the gender of the owner from looking at the name listed as the owner in the land registry records. Approximately 1030 parcels in the sample area were assessed out of an estimated 60,000 total parcels for the island. The number of parcels has been quoted as being 33,000 in 1989 at the end of the systematic adjudication and titling process and 56,000 in 2002 (Barnes and Griffith-Charles 2007). The sample therefore only reflects approximately 1 percent of the total number of parcels in the country but should be reflective of the residential urban/peri-urban parcels in the country. Figure 3.1 shows one example of the blocks with all the registered parcels indicated.

Figure 3.1 - Block 1448B mapsheet

The map sheet indicates that in the peri-urban areas of Babonneau, residential development follows a linear ribbon pattern along the main roadways with larger agricultural parcels falling behind the residential plots.

From the selected blocks in the urban/peri-urban area of Babonneau,

listed as 1446B, 1448B, 1646B 1647B, 1648B, 1846B, 1848B, 1849B, the

parcel owners were determined to be one of the categories of: individual

female, female plus one other, parcels in common, family land, male, or

other, where the owner was some other entity or corporation. These terms

were therefore defined as:

Individual female – The sole owner of the parcel is female

Fem+1 – One female owner plus one other owner (usually a married couple)

Fam – Family land with multiple owners

In Common – Land owned in common by multiple owners in a company or

business

Individual Male – The sole owner of the parcel is male

Other – The land is owned by the state, church or other institution

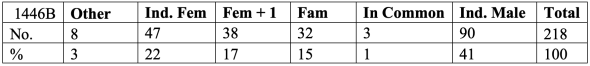

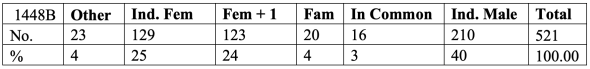

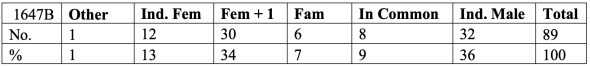

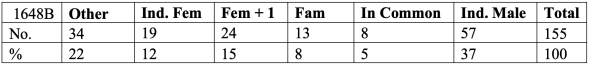

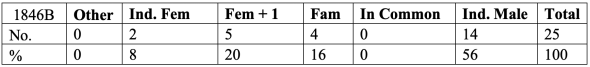

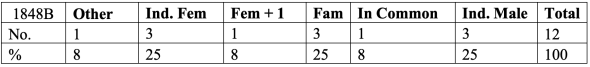

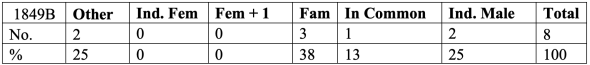

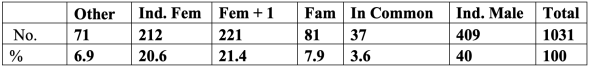

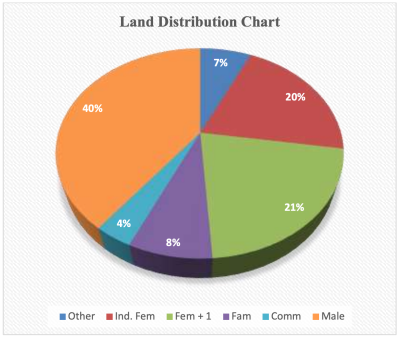

Tables 4.1 to 4.8 indicate the numbers of parcels in each category for each registration block in the land registry while Table 4.9 gives the total of all blocks. Figure 4.1 shows graphically the relative percentages of each category to the total number of parcels. The parcels and percentages in the tables indicate that in each block of parcels, the number and percentages of parcels when the sole owner is male is either almost or more than twice that of the number and percentage of parcels when the sole owner is female. Only in one block is the number equal when the total number of parcels for that block is too few to be representative of the norm.

Table 4.1 - Land distribution data for block 1446B

Table 4.2 - Land distribution data for 1448B

Table 4.3 - Land distribution for 1647B

Table 4.4 - Land distribution for 1648B

Table 4.5 - Land distribution for 1846B

Table 4.6 - Land distribution for 1847B

Table 4.7 - Land distribution for 1848B

Table 4.8 - Land distribution for 1849B

Table 4.9 - total land distribution data

Figure 4.1 - Percentage of parcels per tenure ype of the total number of parcels

From the statistics it is observed that the percentage of individual male owners is almost twice the percentage of individual female owners. The quantitative data, however, does not give the complete picture and more detailed discussions would tease out the impacts of this disparity on the security that female land occupants feel. For example, supportive legislation, where it exists, such as the Cohabitational Relationship Act No. 30 of 1998 (Republic of Trinidad and Tobago 1998), the Distribution of Estates Act No. 28 of 2000 (Republic of Trinidad and Tobago 2000), and the Married Persons Act of 1975 (Republic of Trinidad and Tobago 1976) protect women’s land rights even where their name is not on the title document. The LANDex methodology to determine the perceptions of security require that the respondents answer the following questions for both urban and rural environments.

Number of female respondents that indicated they were “Not worried at

all” about losing rights to use property in next five years

Number of female respondents that indicated they were “Not worried”

about losing rights to use property in next five years

Number of female respondents that indicated they were “Somewhat worried”

about losing rights to use property in next five years

Number of female respondents that indicated they were “Very worried”

about losing rights to use property in next five years

These questions should be answered in further studies using the administration of questionnaires to fully explore the perception of security of tenure that women feel despite the lack of documentary security of tenure equivalent to that of the males. Land administration systems in the Caribbean should seek to ensure that gender information is captured during all land transactions as a part of the standard procedures.

Dr Charisse Griffith-Charles Cert. Ed. (UBC), MPhil. (UWI), PhD (UF), FRICS is currently Senior Lecturer in Cadastral Systems, and Land Administration in the Department of Geomatics Engineering and Land Management at the University of the West Indies, St. Augustine, where her research interests are in land registration systems, land administration, and communal tenure especially ‘family land’. She is also Deputy Dean, Faculty of Engineering (UWI). She places importance on professional membership and is a Fellow of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (FRICS) and member of the Institute of Surveyors of Trinidad and Tobago (ISTT). She has also been President of the ISTT, President of the Commonwealth Association of Surveying and Land Economy (CASLE) Atlantic Region, and President of the Fulbright Alumni Association of Trinidad and Tobago (FAATT). Dr Griffith-Charles has served as consultant and conducted research on, inter alia, projects to revise land survey legislation in Trinidad and Tobago, assess the impact and sustainability of land titling in St. Lucia, address tenure issues in regularising informal occupants of land, and to assess the socio-economic impact of land adjudication and registration in Trinidad and Tobago, apply the STDM to the eastern Caribbean countries, and document land policy in the Caribbean. Her publications focus on land registration systems, land administration, cadastral systems, and land tenure.

Dr Charisse Griffith-Charles

Department of Geomatics Engineering and Land Management

Faculty of Engineering

The University of the West Indies, St. Augustine

TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO

Phone: +868 662 2002 ext 82520

Website:

https://sta.uwi.edu/eng/dr-charisse-griffith-charles