Dr. Frances Plimmer

Abstract

This paper reports on the results of research into the process of

identifying professional competence for surveyors within Europe. Against the

background of the disciplines identified by the World Trade Organisation and

the European Union's Directive on the mutual recognition of professional

qualifications, the use of mutual recognition as a device for securing the

free movement of surveyors throughout Europe is discussed. The role of

professional organisations in implementing mutual recognition and the

different professional activities of surveyors in different European

countries is also presented to improve understanding of both the process of

mutual recognition and the way surveyors become qualified in other European

countries. Potential barriers to mutual recognition and the advantages of

the process, including the culture of surveyors are also discussed.

Introduction

This paper reports on research into how different European countries and

their professional organisations assess professional competence for

surveyors up to and at the point of qualification. This information is used

to develop a methodology to assess professional competence and develop

threshold standards of professional competence for the different areas of

surveying in order to facilitate the movement of professionals within

Europe. Also significant is the existing legislation within the European

Union (EU) which ensures the mutual recognition of professional

qualifications within this specific region of Europe and the current debate

within the World Trade Organisation (WTO) which is developing a similar

system of mutual recognition which can be applied world-wide to providers of

professional services.

Mutual recognition does not affect the ability of an individual to find

employment in another country, although there may be some kinds of surveying

activities which are restricted to surveyors with certain specific

qualifications e.g. licenses. Nor does mutual recognition affect the ability

of surveyors to establish their own companies in other countries, although

once again, there may be restrictions on the kind of work which is

available.

Mutual recognition is a device which allows a qualified surveyor who

seeks to work in other country to acquire the same title as that held by

surveyors who have qualified in that country, without having to re-qualify.

Mutual recognition is, therefore, a process which allows the qualifications

gained in one country (the home country) to be recognises in another country

(the host country).

If the content of professional education and training in both countries

is similar, mutual recognition should mean that a surveyor's qualifications

can be recognised by the relevant professional organisation in another

country. Where the content of professional education and training in both

countries differ significantly, it should mean that qualified surveyors are

required to undertake additional professional education or training (a test

or supervised work experience) to gain knowledge which was not part of their

original professional education and training in order to have a comparable

depth and breadth of professional competence as surveyors who have qualified

through the normal process in the host country. The way the EU administers

its procedure for mutual recognition is discussed later in this paper.

Mutual recognition is perceived by the European Commission as a device for

securing the free movement of professionals within the single market place

of the EU. For the WTO, the aim is the global marketplace for services,

using the process of mutual recognition of qualifications.

With these external pressures on surveying professional organisations, it

is important that information is available to understand, firstly, how

surveyors in different countries acquire their professional qualifications

and secondly, the process by which their professional competence is

assessed.

World Trade Organisation

The creation of a global marketplace for services is one of stated the

aims of the WTO and in recognition of the scale of the task, the WTO has

identified mutual recognition agreements (bi-lateral or multi-lateral) as

the preferred basis for professions to establish or to extend existing

facilities for the free movement of professionals (Honeck 1999). However,

bi-lateral or multi-lateral mutual recognition agreements have only limited

scope (applying only to those countries who are signatories to the

agreement) and may produce a proliferation of different criteria which can

confuse and therefore work against the creation of a global market place for

services.

WTO members have, therefore, agreed to develop specific

"disciplines" which can be applied across the entire range of

professional services sectors, to ensure that national government

regulations dealing with qualification requirements and procedures,

technical standards and licensing requirements do not constitute unnecessary

barriers to trade in services.

Such disciplines aim to ensure that such regulations are:

- based on objective and transparent criteria, such as competence and

the ability to supply the service;

- not more burdensome than necessary to ensure the quality of the

service; and

- in the case of licensing procedures, not in themselves a restriction

on the supply of the service.

Part of the outcome of the WTO's Working Party of Professional Services (WPPS)

was the Guidelines for Mutual Recognition Agreements or Arrangements in the

Accountancy Sector (WTO, 1997) and the Disciplines on Domestic Regulation in

the Accountancy Sector (WTO, 1998a). Both the guidelines and the disciplines

are general in scope and have the potential to be applied across the entire

range of professional services.

To date, the WTO has established "disciplines" (WTO, 1998a)

which should apply to all services as the basis to secure the free movement

of professionals. These are (ibid.):

- transparency (availability of relevant information);

- licensing requirements;

- licensing procedures;

- qualification requirements (which states the equivalence of education,

experience and examination requirements);

- qualification procedures (which require verification of an applicant's

qualifications within a reasonable time scale and also remove residency and

nationality as requirements for sitting examinations); and

- technical standards, which should only fulfil legitimate objectives.

These disciplines (initially prepared for the accountancy sector) require

that any measures ". . . relating to licensing requirements and

procedures, technical standards and qualification requirements and

procedures are not prepared, adopted or applied with a view to or with the

effect of creating unnecessary barriers to trade in . . . services." (WTO,

1998a, at p. 1).

The WTO disciplines are deliberately generic because the WTO intends that

they should be applied to all services, including surveying.

For the purposes of implementing the policy and practice of free movement

of professionals, the surveying profession1) has a number of inherent

disadvantages.

- The professional activities are diverse, encompassing a range of

professional and technical skills, often practised as several professions.

- Not all of these professional activities are grouped together in the

same way as professions in different countries.

- Professional activities which can be performed by surveyors in some

countries are denied to surveyors in other countries.

- Surveying activities which are regulated in some countries are not

regulated in other countries.

- There is a large degree of ignorance in other countries about what

kind of professional activities the different countries' surveying

professions involve.

- There is large degree of ignorance about how different kinds of

surveyors achieve their professional status in different countries.

- Professional organisations in different countries have not yet

achieved an effective and efficient level of communication and co-operation.

There is a degree of similarity between the surveying profession, as

described above and the accountancy profession, as considered by the WTO (WTO

1998b pp 6-8). For example, the scope and form of accountancy regulation

differ widely between countries. There are activities which are regulated in

some countries and not in others and activities which may be performed by

one profession in one country and by another profession in another country.

Regulation of the profession may be at national level or at sub-national

level and imposed either by public or private authorities or both (Honeck,

1999 and WTO, 1998b, p 7). The WTO is keen to ensure that these

characteristics do not impede any international process which seeks to

globalise the provision of professional services.

The WTO's proposals have not yet come into force, but provide a

background to the research and strong guidance as to how the process of

mutual recognition will operate in the future. Of more relevance to this

research in Europe, is the existing European Union (EU) legislation on

Mutual Recognition of professional qualifications.

1) For the purposed of this research the surveying profession is defined in accordance with the FIG 1991 definition, refer Appendix D.

EU Directive on Mutual Recognition

Although not applicable to all of the European countries, the

requirements of the European Union's Directive on the mutual recognition of

professional qualifications (European Council, 1989) cannot be ignored. This

Directive applies to all professions for which a specific sectoral directive

does not exist. In fact, only a few professions have specific sectoral

Directives and these are mainly medical professionals, although architects

are also have their own sectoral Directive which means that an architect

qualified in any member state is automatically qualified in all EU member

states. Thus, the terms of the Directive affect all surveying activities

(and therefore surveyors) except where there is conflict with the activities

of architects.

The Directive is the EU's legal device for securing the free movement of

professionals within the Union and applies only to those individuals who

hold a three-year post-secondary diploma or equivalent academic

qualification. Despite the fact that this research covers the whole of

Europe, the relevance of the EU's Directive is significant. It will be

difficult (if not impossible) for independent professional organisations to

establish a single methodology and procedure to secure professional mobility

which does not reflect the legal requirements of at least part of the

jurisdiction involved.

Thus, the presumption is made that the "surveyor" is not only a

professional (i.e. a practitioner of surveying activities) but also a holder

of an appropriate academic qualification.

The Directive does not, however, require that the diploma held must be

within the same academic discipline as the profession undertaken, merely

that the diploma must prepare the individual for the profession. Thus, it is

possible to hold a diploma in an academic discipline which is unrelated (or

of limited synergy) to the profession undertaken, provided such a diploma is

recognised to have prepared the individual for the profession. The EU's

Directive requires either:

- a diploma required in the home member state for the pursuit of the

profession in question; or

- pursuit of that profession full-time for two years during the previous

ten years in a member state which does not regulate that profession and

evidence of education and training of the appropriate length and level, and

a diploma which provides a means of access to a regulated profession.

The Directive was adopted in order to ensure the free movement of

"professionals". However the terms of the Directive can be

interpreted as defining the "professional" as someone holding

either a profession-specific diploma (without any additional professional

experience) or a diploma (not necessarily profession-specific) plus at least

two years of professional experience. For the purposes of the Directive, the

French interpretation of "professionelle", meaning

"vocational", is adopted. Thus, the Directive does not imply a

level of professionalism, it merely permits applicants to sign up to a code

of professional conduct if one is required of a member of a professional

organisation to which they have applied. Thus, to benefit from the terms of

the Directive, a surveyor should be a practitioner, with a three-year

diploma awarded by a competent authority in one of the EU's member states.

For most surveying activities in most countries, it is evident from this

research (refer later) that only a surveying-specific academic diploma gives

access to the surveying profession. However, this is not universally true.

There are aspects of surveying for which a diploma in, say law or economics,

will give access to surveying employment which itself provides appropriate

education and training to produce the qualified surveying professional (Gronow

& Plimmer, 1992).

In member states where it is necessary to hold a licence in order to

practice as a surveyor, it is for the licensing body to request academic

organisations in each member state to provide details of the content of

academic education which is required for access to their surveying

professions. However, it is for the licensing body to make the decision as

to the appropriateness of the nature and content of the applicant's

professional qualifications.

There is no requirement under the terms of the Directive that the

academic education required prior to qualification should comprise specific

subject matter. All that the Directive requires is a comparative assessment

of the relative content, depth and length of professional education and

training of the "migrant" as compared with that required of a

surveyor newly-qualified in the home member state. The EU Directive

recognises the equivalence of knowledge acquired through an academic diploma

and knowledge acquired though supervised work experience. Thus, no

distinction is made if a particular body of knowledge which is absent from

the academic diploma held by a "migrant", is acquired through

specific work experience and the adaptation mechanisms which allow a

"migrant" to make good any apparent deficiencies of academic or

pre-qualificational knowledge, can be either an aptitude test (examination)

or an adaptation period i.e. a period of supervised work experience.

It is not considered appropriate that any recommended methodology should

include specific consideration of the academic education of the individual,

nor is it considered essential for all surveyors to belong to a professional

organisation in their home countries (although the failure to belong to a

professional organisation where one or more such appropriate organisations

exist in the home country may indicate an absence of a suitable level of

professional competence). Thus, although not necessarily a member of a

surveying professional organisation within the home country, the surveyor

who can benefit under the terms of the Directive from free movement within

the EU member states and whose professional competence requires assessment

is both:

- the holder of a diploma awarded after three years full-time academic

study, by a competent authority, which gives access to the surveying

profession; and

- a practitioner of surveying activities.

From the point of view of implementing the terms of the Directive, it is

necessary to understand how surveyors acquire their professional

qualifications, both the academic and the post-academic processes. The

nature of the procedures and processes of national recognition of surveyors

is well-established in each country, but not generally well-understood by

other countries' surveying professional organisations and one of the main

aims of this research is to improve understanding of how surveyors in

different European countries acquire their professional status as a basis

for establishing the free movement of surveyors.

However, before considering the methodology for assessing professional

competence as a basis for securing mutual recognition of professional

qualifications, there are a number of issues which need to be discussed.

Surveying Activities and Surveying Professions

Surveying, as a profession, has developed in different ways and

encompassing different surveying activities in different countries, in order

to reflect the national needs which have developed over time. Thus, while a

similar range of surveying activities may be undertaken in different

countries, there may be differences between the way these activities are

grouped as a recognised "profession". For example, in the UK, the

activities of urban property agency, development, management, planning and

valuation are grouped as "general practice surveying" for which

there is a recognised academic and professional qualification and title

(Chartered Valuation Surveyor), and thereby these professional activities

comprise one profession. Such activities in France are traditionally shared

between four professionals - the agent immobilier, gérant, expert

immobilier and the conseil juridique (Plimmer, 1991).

Similarly, the content of surveying education and the way it is

structured differs throughout Europe and this is graphically demonstrated in

Professor Mattsson's paper elsewhere in this report (Mattsson, 2001).

It is unreasonable to expect every country to alter the nature of its

surveying profession or its surveying education, unless its own national

consumer or professional interests are served by such changes. Indeed, there

are huge dangers in attempting to harmonise professional education across a

large number of countries. Previous experience within the European Community

in establishing a single sectoral Directive for Architects, which involved

the harmonisation of their academic education across all of the then member

states, took 16 years to achieve and every change in academic content

requires renewed negotiation (Plimmer, 1991).

The implications of the EU directive and the WTO proposals are that it

does not matter how individuals achieve professional status, the important

point is that they have achieved professional status. The only reason to

investigate the nature and content of their pre-qualification process is to

identify any discrepancy between the professional education and training of

the "migrant" with that required of a newly-qualified surveyor in

the host country and therefore to establish an adaptation mechanism to make

good the deficiency.

However, for free movement to take place between member countries, there

must be, what the Directive described as, a corresponding profession i.e. a

substantial similarity between the surveying activities involved in the

surveying professions in both the home and the host countries This is a

matter for the professional organisations in each country to establish and

monitor, as is the professional content of any adaptation mechanism

required.

In the light of the terms of the EU directive and the implications of the

WTO proposals, the ability of surveying professionals to work in other

countries must depend on:

- the existence of a "corresponding profession" i.e. the

extent to which the academic education and professional training and

experience gained in their "home" country matches the surveying

activities comprised in the surveying profession in the "host"

country to which they seek access; and

- the amount of additional academic and/or professional education,

training and experience which they require to demonstrate competence in the

range of surveying activities comprised in the surveying profession in the

"host" country to which they seek access.

Thus, it is necessary for the surveying professional organisations in

each European country to identify which surveying activities are comprised

within their surveying professions and which are therefore required of any

surveyor who wishes to practice that kind of surveying profession in that

country. Comparing such a list of surveying activities with those with which

the surveying applicant is qualified and experienced, also provides the

host-surveying organisation with details of those areas of professional

competence which the applicant is lacking. According to the EU Directive,

such deficiencies can be remedied by either by an aptitude test

(examination) or a period of supervised work experience.

Professional organisations in each country should consider appropriate,

practice-based tasks which can demonstrate that an applicant has made good

any deficiencies in professional education and training and is competent to

practice as a surveyor both in the host country and as a member of the host

professional organisation. The role and responsibilities of professional

organisations in the process of mutual recognition of professional

qualifications is considered in detail later in this report.

Professional Competence

Effectively, what is required by the WTO disciplines and the EU Directive

is an assessment of the professional competence of an applicant (called a

"migrant" in the EU Directive). According to the current

interpretation of the Directive, the standard against which that

professional competence should be assessed is that required of a newly

qualified surveyor in the host member country. It is therefore a major

function of this research to assess what pre-qualificational professional

competence is required of a surveyor in each European country and this has

been extended to include an investigation of the process through which

surveyors gain their qualification - including academic diplomas,

professional work experience, licensing procedures and/or membership of a

professional organisation. The relative processes are discussed later in

this report.

Despite the fact that it is the professional competence of the surveyor

which is fundamental to the ability to practice freely across national

boundaries, it is interesting to consider certain characteristics of the

surveyor as an individual. Thus, it is noted that the definition of a

surveyor, as agreed at FIG's General Assembly in Helsinki, Finland on 11

June 1990 (FIG, 1991 p 9), is ". . . a professional person".

"Professional competence" is extremely hard to define, although

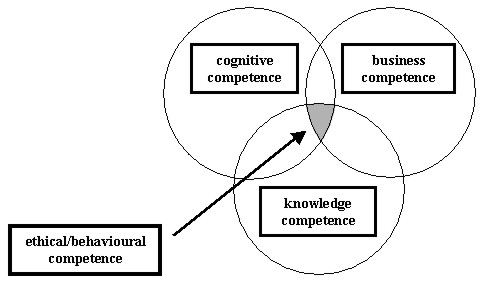

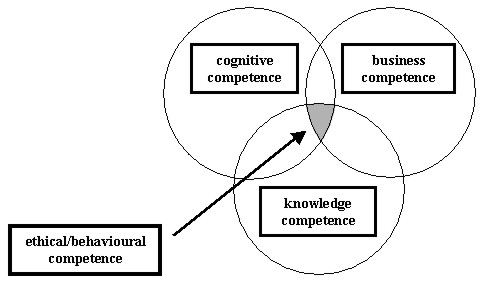

it is something with which all surveyors are familiar. It is suggested (Kennie

et al., 2000) that for newly-qualified surveyors in the UK,

"professional competence" combines knowledge competence, cognitive

competence and business competence with a central core of ethical and/or

personal behaviour competence. Thus:

Source: Kennie, et al. 2000 p. 2

Kennie et al. (ibid. Appendix B pp. 8-9) have defined these component

parts of professional competence, as follows:

- knowledge competence: "the possession of appropriate technical

and/or business knowledge and the ability to apply this in practice";

- cognitive competence: "the abilities to solve using high level

thinking skills technical and/or business related problems effectively to

produce specific outcomes";

- business competence: "the abilities to understand the wider

business context within which the candidate is practising and to manage

client expectations in a pro-active manner"; and

- ethical and/or personal behavioural competence, which is the core to

the other three parts; defined as "the possession of appropriate

personal and professional values and behaviours and the ability to make

sound judgements when confronted with ethical dilemmas in a professional

context".

It may be that for each surveying profession in each European country,

the relative weighting of such components may differ but it is contended

that these four competencies comprise the essence of "professional

competence" for surveyors everywhere.

It is axiomatic that the individual whose competence is being assessed is

a fully qualified professional in the European Country where the

professional qualification was gained (i.e. the home country). However, it

is that individual's competence to work in another European Country (the

host country) which needs to be assessed.

Thus, for the purposes of facilitating professional mobility, it is

necessary to recognise and accept the professional status and the competence

of the applicant in the home country. For the professional organisation in

the host country it is necessary merely to ensure that the applicant is

competent to undertake surveying, as practised in that host country and

therefore to ensure that the applicant is fully aware of and has adapted to

the nature and practice of the surveying profession in the host country.

Therefore the professional organisation in the host country needs to

establish the nature and level of professional competencies within a range

of surveying activities required of a fully-qualified professional in the

host country and to assess the applicant against that content and standard

of professional competence.

For example, The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) which is

one of the UK's professional organisation for surveyors, has a list of

competencies at different levels required of newly-qualified surveyors as an

objective basis of comparison (RICS 2000) which is compiled for its APC

(Assessment of Professional Competence) and this is discussed later.

What is ignored within the current interpretation of the Directive is the

fact that the individual being assessed for this purpose is both a

professional in the country which awarded the original surveying

qualification and a practitioner. Thus, there is no recognition of the

elements of specialisation or expertise which an applicant may have

developed over a number of years practice, and it is both the level and the

areas of knowledge and skill required of a newly-qualified surveyor in the

host member country which an applicant must demonstrate to the competent

authority.

It is suggested that it is for the professional organisation in the home

country to assure other professional organisations of the professional

standing of applicants. This should include such matters as the nature of

the surveying profession pursued by the applicant and their component

activities, the level of the applicant's professional qualification and

statements regarding any action taken by the professional organisation

against the applicant for disciplinary offences.

Once this has been done, it is not for the professional organisation in

the host country to challenge the status and professional integrity of the

applicant. Their role is merely to establish that the applicant has achieved

the appropriate level and range of skills required in the host state, as set

out in an objective list of threshold standards, including (presumably) that

the individual has become fully conversant with and is prepared to observe

the professional ethics and codes of practice it requires.

Role of Professional Organisations

As indicated above, there is a major role for the professional

organisations which award surveyors their surveying qualifications in the

process of mutual recognition.

It is recognised that there are different roles undertaken by

professional organisations. Indeed, for the purposes of this research, it is

appropriate to define the term "professional organisations" by

their function or functions rather than by their names. Thus for the

purposes of this research, "professional organisation" means those

organisations at national or sub-national level which:

- award professional qualifications; and/or

- award practising licenses; and/or

- regulate the conduct and competence of surveyors; and/or

- represent surveyors and their interests to external bodies including

national governments.

In some countries, there is more than one "professional organisation"

as defined above. For example, in Denmark, cadastral surveying can only be

undertaken by surveyors who have a masters-level diploma (bac + 5), who have

undertaken relevant professional work experience and who have been granted a

license by the National Survey and Cadastre (under the Ministry of Housing)

(Enemark, 2001). In the United Kingdom (UK), The Royal Institution of

Chartered Surveyors (RICS) assesses the quality of academic education

through its system of accrediting diplomas (bac + 3), and implements a

system of assessing relevant professional work experience (there is no

licensing system for surveyors in the UK). It is also recognised that in

some European member states, some of these functions are undertaken by

government ministries e.g. the French préfet awards the carte

professionelle license.

In order to achieve the free movement of professionals, judgements need

to be made on the nature of the individual's professional qualification and

experience which is gained in the home country in the light of the nature of

the profession as practised in the host country. Thus, the organisation to

which the individual applies for recognition in the host country needs

sufficient information, firstly, to recognise the nature, scope and quality

of the professional qualification held by the individual and, secondly, to

verify its accuracy. This requires a high level of effective and efficient

communication from the professional organisation in the home country to the

professional organisation in the host country which includes:

- details of the professional qualification held;

- details of the nature of the particular surveying profession to which

the individual's professional qualification gives access; and

- confirmation of the status of the individual's qualification (e.g.

membership level, outstanding fees, expulsion from the organisation).

Ideally, this should be based on a simple questionnaire which could be

sent (via e-mail) to the relevant organisation which should have a

standardised procedure to ensure both accuracy and speed of response.

There should be sufficient information, available in the public domain,

to ensure appropriate understanding of the responses received, which may not

always be in the language of the host country.

Thus, a vital role of each professional organisation is the provision of

information relating to the nature of professional qualifications, the

nature of the various surveying professions for which each is responsible, a

database and a procedure which allows a rapid and accurate response to

requests for information about particular individuals.

Also, each professional organisation should also have a procedure which

requests and deals with requests for the above information and processes

them, together with the applicant's request for mutual recognition, in an

efficient and effective manner.

Ultimately, it will be for the professional organisation to establish

what, if any, additional professional education and/or training is necessary

before a particular applicant is able to practice within the host country in

the light of the threshold standards applied to newly-qualified nationals.

However, there is a problem of requiring an experienced practitioner to

demonstrate the same breadth of professional skill and knowledge over the

range of threshold standards required of a newly qualified surveyor in the

home country. During the course of a professional career, it is not

unreasonable to expect professionals to develop high levels of expertise in

some areas at the expense of others. It may be extremely difficult (and

certainly daunting) for such practitioners to acquire and demonstrate the

full range of skills required of a newly qualified national in the host

country.

It is, therefore, suggested that, in the light of the implicit

professionalism of the applicant and the recognition of the distinction

between the nature of the surveyor's competence at the point of

qualification and subsequently during (what for some is) a long and varied

career, a pragmatic approach should be taken which ensures that the

applicant can demonstrate the adaptation of existing surveying skills to a

new working environment (including perhaps new ethics and codes of

practice), together with a broad understanding of the other surveying

activities and issues which affect the profession in the host member

country.

However, it is likely that, with the aim of being seen to maintain high

quality of services and products, the most contentious issues for surveyors

and their professional organisations will not be the comparability of

professional activities, or the level and scope of professional education

and training, but the exact nature of the compensatory measures required

which must be left to the professional organisations concerned to consider.

Thus, the role of professional organisations is vital if free movement of

professionals through the mutual recognition of qualifications is to be

achieved.

Barriers and Hurdles

Although not of direct relevance at present, the potential impact of the

WTO disciplines as a device for achieving mutual recognition of

qualifications and thereby free movement of professionals and the EU's

Directive on mutual recognition have informed this discussion. The

inevitability of WTO legislation to ensure the free movement of surveyors on

a global basis is assumed, as is the presumption that if a methodology can

be established within a European context, such a methodology can be applied

world-wide. This does not, however, mean that the process will be easy,

either in theory or in practice.

There are major issues of principle (not the least of which is that of

mutual recognition itself) which professional organisations on behalf of

their own countries need to embrace and embrace with commitment. However,

professional organisations are frequently held back by bureaucracy and by a

potential conflict of views between ministry rules with which professional

organisations do not always agree. Thus appropriate ministries should be

included in any discussions on mutual recognition processes. Certain

principles will cause great difficulties. It is suggested, for example, that

the apparent equivalence (according to the EU Directive) of academic testing

and professional practice and experience to make up any deficiency in

professional knowledge will challenge traditional professional education

principles.

There are, however, a number of principles which should be observed, and

these include the absence of any form of discrimination against any

individual surveyor simply because qualification has been earned in another

country. Indeed, this is a requirement within the WTO disciplines proposed (WTO,

1997 and 1998a). Assuming that the professional organisations which

represent surveyors and which monitor their qualifications fulfil their

responsibilities fairly and professionally, there should be little problem

in administering the process of mutual recognition of qualifications.

Similarly, it will be necessary to ensure that practising licenses, which

are normally awarded to those professionals who have achieved an appropriate

level of academic (or academic and professional) qualification and who are

required to demonstrate often to a government-appointed authority, the

quality of their professional practice skills, are awarded solely on the

basis of professional competence to practice in that country and not on any

basis which discriminates against those who are professionally training and

experienced in another country.

It seems that in some countries where the award of a practising license

is required, only those holding certain qualifications are permitted to

apply. Again, provided that no distinction is made by the licensing

authority between those applicants whose qualifications were gained in the

host country and those who have acquired their qualifications by a process

of mutual recognition, that all are required to undergo a similar process

and demonstrate similar levels of professional competence in order to

acquire practising licenses, there should be no unreasonable barriers to the

free movement of professionals.

However, it is recognised that we are all products (to a greater or

lesser extent) of our national and professional backgrounds and the various

cultural influences which affect how we work and why we undertake our

professional activities in the way we do. In order to achieve any kind of

dialogue, these differences, particularly those in professional practice,

and those which affect inter-personal relationships, need to be

investigated, understood and respected.

The most obvious barrier to the free movement of surveyors is language,

but access to learning different languages is normally dependent on

individual opportunity and effort, and, initially, on national primary and

secondary education systems which can provide either a very positive or

rather negative lead. Language skills are, however, vitally important to

permit international communication and genuine understanding of the rich

variety of professional and personal life-styles. As such, it is a barrier

which can be overcome, although it is suggested that the real

"language" barrier will be in establishing the technical meaning

of the educational and professional jargon e.g. the meaning of

"diploma" in continental Europe is not the same as that used in

the UK and in Ireland.

However, there is also the matter of culture which permeates our national

or regional societies and which comprises a series of unwritten and often

unconscious rules of conduct, professional practice and of perceived

relationships. Failure to understand and observe the cultural norms of other

people can result in confusion, hurt and, at worse, perceived insult, and

there is evidence that culture divides us, both as individuals (as the

products of our nation's upbringing) and also as surveyors (as the products

of our professional background).

Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner (1997), in a work which illustrates that

many management processes lose effectiveness when cultural borders are

crossed, describe the nature of specific organisational culture or

functional culture (ibid. pp 23-4) as ". . . the way in which groups

have organised themselves over the years to solve the problems and

challenges presented to them." Based on the historical and original

need to ensure survival within the natural environment, and later within our

social communities, culture provides an implicit and unconscious set of

assumptions which control the way we behave and expect others to behave.

Thus, "The essence of culture is not what is visible on the surface. It

is the shared ways groups of people understand and interpret the

world." (ibid. p 3), and as surveyors, although we all perform similar

functions and provide similar services to our clients, we achieve these by

different means.

This paper contends (as do Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner (1997)) that

the fact that we use different means is irrelevant. What is important is

that we perform similar functions and provide the services professionally

(efficiently, effectively and within an ethical context) and to the

satisfaction of our clients. However, to ensure the mutual recognition of

professional qualifications, cultural differences need to be recognised in

order to understand and accept that surveyors in different countries have

different perceptions as to the nature of professional practice and the

routes to professional qualifications.

The research has identified discrepancies between the professional

activities undertaken by different kinds of surveyors in different European

countries, with some kinds of surveying activities demonstrating a greater

or lesser degree of international commonality (refer later). It is contended

that there is nothing wrong with difference, it merely has to be recognised

and accommodated within whatever system is devised for the creation of the

free movement of professionals.

Threshold Standards of Professional Competence for the Different Areas

of Surveying

Threshold standards are those academic and/or professional qualifications

required of a newly qualified surveyor. They can be identified by reference

to such achievements as a particular academic award, a period of

professional work experience, the holding of a licence or membership of a

professional organisation and, for the purpose of comparison between

different countries, should be defined by reference to the professional

competencies which the "qualified" surveyor has achieved.

It must be recognised that, in some countries, there are different kinds

of surveyors whose professional education and training follows different

routes and therefore for the purposes of this research, it is necessary to

investigate the professional competencies for each kind of surveyor in each

European country.

However, threshold standards of professional competence for the different

areas of surveying cannot be investigated until certain other issues have

been identified. Thus, it is necessary to identify for each European

country:

- the nature of the various distinctive surveying professions which are

pursued within its borders. The identification of distinctive surveying

professions should be established based on, amongst other things, routes to

qualification, licensing arrangements, professional organisations involved

and professional activities;

- the main professional activities pursued within each distinctive

surveying profession. This research has used the FIG definition of

"surveyor" (FIG, 1991) to identify these activities, although it

seems likely that an extended version of this definition will be necessary

to reflect the detailed activities involved in some areas of construction

and management and also to reflect the evolving nature of surveying since

the definition was originally adopted;

- how professional qualification and/or licensing is achieved for each

distinctive surveying profession and the role of professional organisations

in each European country, including any requirements, such as professional

indemnity insurance, adherence to codes of conduct; and

- the level of competence required for each of the main professional

activities. It is suggested that this requirement will be extremely hard to

achieve. Levels of competence are, to a large extent, subjective, unless of

a highly technical nature and therefore easily proven (e.g. correctly

identify all symbols on a map). In any event, the current EU interpretation

of what should be identified are the skills and knowledge required of a

newly-qualified surveyor, which ignores the development of the more focused

but in-depth range of knowledge and expertise of a mature professional.

It is likely to be a requirement that all applicants hold either a

diploma in a relevant surveying profession or a diploma which gives access

to the surveying profession in their home country (see above). Most of the

issues cited above require the provision of factual information from

professional organisations in European countries. There are two main issues

which need to be discussed.

Professional Competence of a Practitioner

While it may be relatively straightforward to identify the professional

activities and level of knowledge and skill required of a newly-qualified

surveyor, it is very different to assess the appropriate breadth and depth

required in the knowledge and skill of an experienced practitioner.

It is suggested that very few professionals (if any) retain and maintain

the original level of skill and knowledge across the full breadth of

professional activities which is normally required at the time of

qualification. It is not unusual for surveyors to begin their professional

careers by experiencing different kinds of professional activities before

specialising in a limited range of professional activities and it is

hypothesised that the majority of surveyors specialise in one or several

areas of professional practice which then become the focus of their careers.

While some organisations may require practitioners to keep up-to-date on

changes affecting areas of professional practice, it is not reasonable to

expect surveyors to maintain the same breadth and depth of knowledge as that

achieved on qualification. Levels of expertise in some areas are matched by

levels of relative ignorance in others, particularly in new developments in

those areas. Surveyors remain "competent" because they work within

their areas of expertise and do not undertake work for which they do not

have sufficient up-to-date knowledge and skill. Indeed, they would be

negligent and unprofessional were they to do otherwise.

Thus, the practitioner whose competence is being assessed in another

member country, is likely to be an experienced practitioner in a range, but

not in all, of the areas of professional practice which comprise the

surveying profession in the home country, and it is as an experienced

professional that the applicant should be assessed. However, the current

interpretation of the Directive expects the applicant to demonstrate a full

range of knowledge and skill across all aspects of the surveying profession

as practised in the host country which can, therefore, be measured against

the list of competencies required of a newly qualified surveyor. It is

contended, however, that this approach discriminates against the more mature

and experienced migrants for whom it should merely be necessary to establish

that, within the areas of expertise in which they are experienced and in

which they practice, they are competent to undertake those professional

activities in the host country and that they are aware of the broader issues

which affect the profession of surveying in the host country.

In other words, it should be necessary merely to ensure that, as a

surveying professional with a range of expertise, the applicant has adapted

that range of expertise to a foreign working environment and is therefore

"competent" to practice in the host country and to acquire the

relevant surveying title and/or qualification. Current interpretation of the

Directive, however, requires that all migrants are assessed against the

standard applied to a newly qualified surveyor in that member country, and

therefore it is vital to investigate the threshold standards applied to

newly qualified surveyors in Europe.

Professional Nature of Practitioner

The concern for competence is generally considered to be that of the

professional organisation and the other surveyors in the host country. It is

certainly likely to be the responsibility of the host country to assess the

professional competence of the applicants. However, it is suggested that the

applicant too is concerned to demonstrate competence, not merely to secure

the title or qualification of the host country, but also because of the high

moral code of conduct required of a professional within Europe.

Historically, the nature of a "professional" implied high moral

conduct and provided a standard of service on which the public and

governments relied to ensure socially correct and ethical behaviour.

Recently, professional organisations impose codes of conduct on their

members, and it is the resulting level of conduct and moral behaviour which

provides the very core of the status accorded to professionals (refer Kennie,

at al. 2000).

However, it seems that it is not always possible to rely on professionals

to behave in an ethical manner and therefore, professional organisations

have a responsibility to ensure that professionals are competent and remain

so. The external imposition of ethical behaviour is particularly important

for employees who may be forced to undertake a particular professional

activity as part of their employment for which they have not received

adequate education or training.

UK Experience of Mutual Recognition procedure

It must be recognised that the applicant seeking to move from one

European country to another is a fully qualified professional and cannot be

expected to re-qualify in another country. Indeed, the principles of mutual

recognition of qualifications specifically seek to avoid this. Thus, for the

purposes of mutual recognition, it may be that requirement (d) above is

superfluous.

Experience in the UK since the introduction of the terms of the Directive

and the various reciprocity agreements entered into by The Royal Institution

of Chartered Surveyors show that, without exception, all applicants have

obtained employment within the surveying profession in the UK and have

sought to adapt their existing professional expertise to the conditions and

practice within the UK. Difficulties have arisen where the nature of the

profession as practised in the UK differs from that practised in the home

country and adaptation mechanisms have been imposed. However, it has been

necessary to require the applicants to demonstrate the breadth and depth of

knowledge within their chosen areas of expertise as well as in other

professional activities which comprise the particular kind of surveying

profession in question.

However, what is suggested is that the professional profile of each

applicant should be considered in the light of the totality of the academic

and professional education, training and experience gained in the home or

any other EU country as at the date of application. A comparison can then be

made between this level and degree of professional competence and:

- the level of knowledge and skill required of an experienced

practitioner in the host country to perform the range of professional

activities with which the applicant is familiar and which is comprised

within the surveying profession for which the applicant seeks access; and

- the level of knowledge and skill which a practitioner in the host

country who is not experienced in those professional activities with which

the applicant is unfamiliar but which are comprised in the surveying

profession for which the applicant seeks access.

Where an applicant does not have the necessary knowledge and skill to

undertake a relevant professional activity, an appropriate adaptation

mechanism, either supervised work experience or an examination, can be

required. It should be noted that the EU directive does not permit competent

authorities to require an examination as the adaptation mechanism for

surveyors. Having been required to remedy a deficiency in certain areas of

professional activities, the applicant surveyor is free to choose whether to

do this by supervised work experience or by undertaking an examination.

In order to achieve consistency and to avoid any legal conflict, and in

the light of WTO's recognition of the equivalence of education, experience

and examination requirements, it is suggested that a similar approach is

adopted i.e. that the applicant can choose between either an examination or

a period of supervised work experience. In either case, it must be possible

for an applicant who does not achieve the appropriate level of competence to

fail.

Threshold Standards in Europe

In order to identify threshold standards applied to surveyors in Europe,

a questionnaire was devised and distributed to attendees at the joint CLGE/FIG

seminar in Delft 2) . The questionnaire which was piloted at the Delft seminar

and amended subsequently, sought to identify issues of comparability in the

nature of the work of geodetic surveyors in Europe, the nature of their

academic and professional pre-qualification process and to identify any

threshold standards applied to newly-qualified surveyors.

2) Enhancing Professional Competence of Geodetic Surveyors in Europe a joint CLGE/FIG seminar held in association with the Department of Geodesy, Delft University of Technologu, 3rd November 2000.

Analysis of Questionnaires

The questionnaire distributed to the delegates at the Delft seminar is

included with this paper. The response rate was 51%, covering 16 of the 20

countries (only Italy, Latvia, Norway and Slovenia are omitted).

1. Professional Activities

In investigating the activities which surveyors in Europe undertake, the

FIG definition (FIG, 1991) was used because it is a widely used

international definition in languages other than English. The analysis

revealed that, with the exception of Belgium and Luxembourg, all surveying

respondents considered the following to be the activities of surveyors in

their countries:

(1) the science of measurement;

(2) to assemble and assess land and geographic related information;

(3) to use that information for the purpose of planning and implementing the

efficient administration of the land, the sea and structures thereon; and

(4) to instigate the advancement and development of such practices.

Practice of the surveyor's profession may involve one or more of the

following activities which may occur either on, above or below the surface

of the land or the sea and may be carried out in association with other

professionals:

(5) the determination of the size and shape of the earth and the

measurement of all data needed to define the size position, shape and

contour of any part of the earth's surface;

(6) the positioning of objects in space and the positioning and monitoring

of physical features, structures and engineering works on, above or below

the surface of the earth;

(7) the determination of the position of the boundaries of public or private

land, including national and international boundaries, and the registration

of those lands with the appropriate authorities;

(8) the design, establishment and administration of land and geographic

information systems and the collection, storage, analysis and management of

data within those systems; and

(13) the production of plans, maps, files, charts and reports.

Belgium excluded (5) (the determination of the size and shape of the

earth and the measurement of all data needed to define the size position,

shape and contour of any part of the earth's surface); (6) (the positioning

of objects in space and the positioning and monitoring of physical features,

structures and engineering works on, above or below the surface of the

earth); and (8) (the design, establishment and administration of land and

geographic information systems and the collection, storage, analysis and

management of data within those systems).

Luxembourg also excluded (4) the instigation of the advancement and

development of measurement etc. practices

With regard to the other activities ((9) the study of the natural and

social environment, the measurement of land and marine resources and the use

of the data in the planning of development in urban, rural and regional

areas; (10) the planning development and redevelopment of, whether urban or

rural and whether land or buildings (11) the assessment of value and the

management of property, whether urban or rural and whether land or

buildings; (12) the planning, measurement and management of construction

works, including the estimation of costs), Belgium, and Luxembourg together

with Ireland excluded (9) the study of the natural and social environment,

the measurement of land and marine resources and the use of the data in the

planning of development in urban, rural and regional areas; although

responses from the Netherlands were contradictory.

The Czech Republic, Spain, Ireland, and Luxembourg, excluded (10) the

planning development and redevelopment of, whether urban or rural and

whether land or buildings and, once again, responses from the Netherlands

were contradictory.

However, only France, Greece, Luxembourg, Sweden and the UK included (11)

the assessment of value and the management of property, whether urban or

rural and whether land or buildings; and only Austria, France, the Slovak

Republic, Switzerland and the UK included (12) the planning, measurement and

management of construction works, including the estimation of costs. Once

again, the responses from the Netherlands were contradictory.

Additional activities mentioned by respondents included photogrammetry

and remote sensing (Spain, Greece, Slovak Republic) with the Czech surveyors

responsible for the standardisation of names of settlements; the Spanish

surveyors responsible for geophysical prospection and industrial

applications of surveying; the Greek surveyors including road planning and

hydraulic work and the Slovak Republic including geodynamic monitoring. The

UK also include property investment analysis and portfolio management as an

activity related to (11) the assessment of value and the management of

property, whether urban or rural and whether land or buildings; and the

planning and implementation of the repair, maintenance and refurbishment of

existing buildings, which is an activity undertaken by building surveyors.

It should be pointed out that in the UK although all of the surveying

activities listed are practised by surveyors, those surveyors qualified to

do activities (1) - (8) (land or geomatic surveyors) are not also qualified

to undertake work in the other areas. Similarly, the qualification of the

quantity surveyor or construction economist (12) does not include any of the

other activities (except for the production of plans, reports etc. (13));

and the qualification of general practice surveyor or valuation surveyor

(11) does not include other activities (except for (13)). Thus, while all of

the activities are practised in the UK by surveyors, the professional

activities and therefore the academic and professional education and

training, differs between some seven different kinds of surveyors and it is

not usual for a surveyor to be qualified in more than one specialisation.

In summary, it seems that the activities of (11) the assessment of value

and the management of property, whether urban or rural and whether land or

buildings; and (12) the planning, measurement and management of construction

works, including the estimation of costs are those which are least common

throughout the respondent countries, with widespread commonality regarding

the various surveying activities of land measurement and management.

2. Regulation and Licensing

There is evidently a variety of regulatory and licensing arrangements in

the countries surveyed. Some countries e.g. Luxembourg, Netherlands and

Sweden reported no regulatory organisations and France, Ireland, Luxembourg,

Switzerland, the Netherlands and the UK reported no licensing organisation.

In Germany, both regulation and licensing are a function of the government

at state-level.

It should be noted that although the UK recognised The Royal Institution

of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) as a regulatory organisation, there is no

control over surveyors and surveying activities in the UK. The RICS merely

controls the title of "Chartered Surveyor" but there is no

legislative requirement in the UK for any kind of surveying activity to be

undertaken by a Chartered Surveyor.

3. Academic Education

There is a predominance of bac+5 as a prerequisite for entry into the

"Ing" level of the surveying profession after tertiary education.

Only the UK reported an entry level as low as bac+3. Ireland requires bac+4

as do two Hogeschools in the Netherlands. Sweden requires bac+4.5.

In the light of the breadth of professional activities for which these

students are educated and trained, it is not surprising that the academic

education lasts for five years. The comparatively narrow and specialist

nature of UK academic surveying education perhaps explains the bac+3

process.

4. Additional Requirements

Only Belgium, Spain, Greece, the Netherlands and Sweden reported no

requirement for post-university work experience prior to qualifications. The

duration of such work experience for those countries which required it

ranged from one year (Switzerland) and five years (Slovak Republic), with

two or three years being common.

Only Austria, Greece and the Slovak Republic required membership of a

professional organisation, while the Czech Republic, Luxembourg and

Switzerland required the taking of a state examination. Six countries

reported a limit on the nature of work undertaken by pre-qualified surveyors

and this relates almost entirely to their inability to undertake cadastral

work.

5. Threshold Standards

Although it was recognised that the requirement to hold a certain

academic qualification and/or pass a state examination were "threshold

standards", only the UK, through The Royal Institution of Chartered

Surveyors imposes specific threshold standards after the award of a bac+3

accredited University degree and two years of supervised work experience.

These threshold standards, which the RICS calls "competencies" are

explicitly documented and specifically tested during the surveying

applicant's supervised work experience by the employer and at the point of

qualification by the RICS in its Assessment of Professional Competence.

These competencies vary for the different divisions or specialisms of the

RICS and are divided (RICS, 2000) into:

- Common Competencies, which are common to all surveyors, regardless of

specialism: and comprise Personal and Interpersonal Skills; Business Skills;

Data, Information and Information Technology; Professional Practice; Law;

Measurement; and Mapping;

- Compulsory Core Competencies, which differ depending on the

specialism and which are categorised into three levels. Thus, for Geomatics,

the compulsory core competences are Data Capture; Spatial Data Presentation

and at least one (at level 3) of Cadastre, Cartography, Engineering

Surveying and Monitoring, Geodesy and Geophysics, GIS/LIS, Hydrography,

Oceanography, Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, Surveying land/sea;

- Optional Competencies, which are additional to the Core Competencies.

At least two further optional competencies (one at level 1 and one at level

2) are required from the Compulsory Core Competencies listed in (b) above

(being Cadastre, Cartography, Engineering Surveying and Monitoring, Geodesy

and Geophysics, GIS/LIS, Hydrography, Oceanography, Photogrammetry and

Remote Sensing, Surveying land/sea) together with Contract Administration,

Drawings, Ground Engineering and Subsidence, Project Management and

Technologies, Sea and Seabed Use.

Each of these competencies (and those specified for the other specialisms)

are defined (ibid.) in relation to three levels. Thus, Cadastre is defined

(ibid. p. 17), thus:

"Level One- define field and office procedures for boundary surveys,

identify legal and physical boundaries and provide evidence of boundaries.

"Level Two- demonstrate an understanding and related use of the

principles of land registration and legislation related to the rights in

real property. Understand the surveyor, client and legal profession

relationship and the preparation of evidence for the legal process.

"Level Three- demonstrate a full appreciation of the activities and

responsibilities' / of the expert witness. Understand the resolution of

disputes by litigation and alternative procedures."

Thus, a Geomatics candidate for the Assessment of Professional

Competence, could choose to demonstrate competence in level one or level two

Cadastre as one of the optional competencies; or level three Cadastre as a

Compulsory Core Competency. Alternatively, a Geomatics candidate can choose

to demonstrate other competencies and avoid Cadastre altogether.

This process relies heavily on the employer, firstly to ensure that the

candidate is experienced in the appropriate range and level of competencies

and, secondly, to certify that the candidate has gained the appropriate

standard in each competency. The additional requirements of the Assessment

of Professional Competence, including a written submission and presentation,

diary and log book and interview, give the RICS's Assessors the opportunity

to verify the candidate's achievements. The process is monitored by the RICS,

employers are supported by specialist advisors and APC Assessors (qualified

and experienced surveyors) are trained to ensure uniformity and quality of

testing.

The very uniqueness of this system in the UK justifies the detail with

which it is presented here. As a statement (or series of statements)

describing the professional activities of surveyors, it is extremely useful,

and demonstrates a device for ensuring and testing professional practice as

an alternative to academic-style examination at the point of professional

qualification.

However, it can be argued that, as a process, it is flawed. It is highly

mechanistic and it places huge responsibilities on employer practitioners

who are encouraged, (but not required), to provide structured professional

training, supervision and counselling for their graduate employees.

Employers are not trained in this educational role (although there is access

to a Regional Training Advisor for assistance), nor is any sanction imposed

on the employer if the quality of training and/or assessment is inadequate.

In principle, the combination of academic education and professional

training should be appropriate for qualified surveyors and many countries in

Europe require such a process. However, the research has demonstrated a

range of processes for acquiring professional status, from the holding of an

academic qualification only (e.g. Spain and the Netherlands) to a mixture of

academic education and professional experience (e.g. Czech Republic and

Denmark). Some countries include a requirement to belong to a professional

organisation (e.g. Ireland and Switzerland) and some add a licensing system

(e.g. Austria and Slovak Republic).

Such information is vital if we are to understand how surveyors acquire

their qualifications and therefore understand how mutual recognition can

work in Europe. Mutual recognition of professional qualifications is not a

reason for any country to change the way its surveyors acquire their

professional qualifications, although we can benefit from understanding the

systems and processes adopted by each other.

Methodology for Professional Organisations

It should be evident from the earlier discussions in this paper, that

there is a role for professional organisations and specific actions which

such organisations should take in order to ensure effective and efficient

free movement of professional surveyors world-wide.

The underlying issue of mutual recognition is not the awarding of

qualifications from other countries, but the rights to practice one's

professional skills in those other countries. The awarding of qualifications

(and the right thereby to apply for appropriate licenses) is merely a device

for ensuring that only appropriately qualified individuals have access to

regulated professional activities.

Professional Organisations

It is recognised that, throughout the world, there are different roles

undertaken by professional organisations. Indeed, for the purposes of this

paper, it is perhaps appropriate to define the term "professional

organisations" by their function or functions rather than by their

names (refer above).

In some countries, there is more than one "professional organisation"

as defined above. For example, in Denmark, surveyors gain professional

qualifications from the Den danske Landinspektørforening but a license to

practice is awarded by the National Survey and Cadastre (under the Ministry

of Housing). In the Ireland, The Society of Chartered Surveyors fulfils all

of these roles (there is no licensing system for surveyors in the Ireland).

The following considers each of these roles which professional

organisations currently undertake and discusses their relevance to mutual

recognition.

1. Professional Qualification:

In order to achieve the free movement of professionals, judgements need

to be made on the nature of the individual's professional qualification and

experience which is gained in the home country, in the light of the nature

of the profession as practised in the host country. Thus, the organisation

to which the individual applies for recognition in the host country needs

sufficient information, firstly, to recognise the nature, scope and quality

of the professional qualification held by the individual and, secondly, to

verify its accuracy. This requires a high level of effective and efficient

communication from the professional organisation in the home country to the

professional organisation in the host country which includes:

- details of the professional qualification held;

- details of the nature of the particular surveying profession to which

the individual's professional qualification gives access; and

- confirmation of the status of the individual's qualification (e.g.

membership level, outstanding fees, expulsion from the organisation).

Ideally, this should be based on a simple questionnaire which could be

sent (via e-mail) to the relevant organisation which should have a

standardised procedure to ensure both accuracy and speed of response.

There should be sufficient information, available in the public domain,

to ensure appropriate understanding of the responses received, which may not

always be in the language of the host country.

Thus, a vital role of each professional organisation is the provision of

information relating to the nature of professional qualifications, the

nature of each of the surveying professions for which each is responsible, a

database and a procedure which allow a rapid and accurate response to

requests for information about particular individuals.

Also, each professional organisation should have a procedure which

requests the above information and processes it, together with the

applicant's request for mutual recognition, in an efficient and effective

manner.

2. Award practising licenses:

Practising licenses are normally awarded to those professionals who have

achieved an appropriate level of academic (or academic and professional)

qualification and who are required to demonstrate often to a

government-appointed authority, the quality of their professional practice

skills.

It seems that in countries where the award of a practising license is

required, only those holding certain qualifications are permitted to apply.

Provided that no distinction is made by the licensing authority between

those applicants whose qualifications were gained in the host country and

those who have acquired their host qualifications by a process of mutual

recognition, that all are required to undergo a similar process in order to

acquire practising licenses, there should be no unreasonable barriers to the

free movement of professionals.

3. Regulate the conduct and competence of surveyors:

It is implicit in the award of a professional qualification that the

individual has demonstrated a level of (academic and/or professional)

competence and it may be an implicit or explicit requirement that the

individual will observe an appropriate code of conduct and ethics. If an

individual fails to maintain an appropriate standard of competence and/or

fails to observe an appropriate code of conduct or ethics, then the

professional organisation may have the power to impose disciplinary measures

and such an individual may be suspended or expelled from membership of the

organisation.

Such an individual should not be entitled to use the benefits of mutual

recognition to practice in another country. Since the individual's original

certificate of qualification will not indicate subsequent suspensions or

expulsions, it is only by receiving relevant information from the

professional organisation in the home country that the host professional

organisation can establish that the applicant is of good standing and such

information as may be appropriate should be made available on request.

4. Represent surveyors and their interests to external bodies including

national governments.

With increasing globalisation, there are growing requirements for

professional organisations to represent the views of surveyors to

international external bodies. While not vital to securing mutual

recognition of professional qualifications, increasingly it seems likely

that professional organisations will need to work together to represent the

views of their members and their interests to international external bodies.

Such co-operation will provide an additional vehicle whereby professional

organisations can enhance their mutual understanding and thereby facilitate

the whole process of mutual recognition of professional qualifications.

Professional associations range from strictly government bodies to

completely private organisations. Their activities may encompass any or all

of a wide range of functions, including examinations and authorisations,

education and training, professionals standards, disciplinary measures,

quality control, providing various membership services and representing the

profession. They can represent their members at local, national, regional

and international levels.

Similarly, the legal forms for the practice of activities, licensing and

professional qualification requirements vary, although the underlying

reasons for such controls, e.g. to ensure liability and prevent conflicts of

interest, consumer protection, respect of relevant laws and regulations,

remain the same.

Other common requirements relate to professional education and training,

indemnity insurance, absence of a criminal record, proof of membership of a

professional organisation, residency and citizenship requirements.