Article of the Month -

December 2010

|

From Cadastre to Land Governance in Support of the

Global Agenda - The Role of Land Professionals and FIG

Stig ENEMARK, FIG President 2007-2010

Professor in Land Management, Aalborg University, Denmark

This article in .pdf-format (23

pages, 3.29 MB)

This article in .pdf-format (23

pages, 3.29 MB)

1) The paper facilitates an

understanding of how the cadastral concept has evolved over time into

the broader concept of Land Administration Systems in support of sound

Land Governance. The role of land professionals and FIG is underlined in

this regard. The paper also represents the essence of a range of papers

presented by the author as President of FIG over the term of office

2007-2010.

1. INTRODUCTION

In most countries, the cadastral system is just taken for granted,

while the impact of the system in terms of facilitating an efficient

land market and supporting effective land-use administration is not

fully recognised. The reality is that the impact of a well-functioning

cadastral system can hardly be overestimated. A well-tailored cadastral

system is in fact acting as a backbone in society.

The famous Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto has put it this way:

“Civilized living in market economies is not simply due to greater

prosperity but to the order that formalized property rights bring” (De

Soto, 1993). The point is that the cadastral system provides security of

property rights. The cadastral systems thereby paves the way for

prosperity – provided that the basic land policies are implemented to

govern the basic land issues, and provided that sound institutions are

in place to secure good governance of all issues related to land and

property. This institutional context is of course country unique.

Since the early 1990´s there has been a major evolution in this area

of land administration. FIG has played a significant role in terms of

facilitating the understanding of the role of land administration, and

by establishing a powerful link between appropriate land administration

and sustainable development.

2. EVOLUTION OF CADASTRAL SYSTEMS

Throughout the world, the cadastral concept has developed

significantly over the past few decades. The most recent examples are

current world concerns of environmental management, sustainable

development and social justice.

The human kind to land relationship is dynamic and is changing over

time as a response to general trends in societal development. In the

same way, the role of the cadastral systems is changing over time, as

the systems underpin these societal development trends. In the Western

world this dynamic interaction may be described in four phases as shown

in figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Evolution of Western Cadastral System (Developed from

Williamson and Ting, 1999)

Over the last few decades land is increasingly seen as a community

scarce resource. The role of the cadastral systems has then evolved to

be serving the need for comprehensive information regarding the

combination of land-use and property issues. New information technology

provides the basis for this evolution. This forms the new role of the

cadastral systems: the multi-purpose cadastre.

2.1 The FIG Agenda

The international development in the area of Cadastre and Land

Administration has been remarkable with FIG taking a leading role.

Throughout the last 10-15 years a number of initiatives have been taken

with a focus to explain the importance of sound land administration

systems as a basis for achieving “the triple bottom line” in terms of

economic, social and environmental sustainability. International

organizations such as UN, FAO, HABITAT and especially the World Bank

have been key partners in this process.

The International Federation of Surveyors (FIG, 1995) defines a

cadastre as a “parcel based and up-to-date land information system

containing a record of interests in land (e.g. rights, restrictions and

responsibilities). It usually includes a geometric description of land

parcels linked to other records describing the nature of the interests,

ownership or control of those interests, and often the value of the

parcel and its improvements. It may be established for fiscal purposes

(valuation and taxation), legal purposes (conveyancing), to assist in

the management of land and land-use control (planning and

administration), and enables sustainable development and environmental

improvement”.

A rage of publications is presented below showing the impact of the

FIG agenda.

|

In 1995 FIG published an important and very

timely publication entitled “The FIG statement on the Cadastre”.

In many countries throughout the world the cadastral systems

were revised, mainly due to technology development. Cadastral

reform was on the agenda in most developing countries. At the

same time, there was also an increasing focus on the cadastral

systems in Eastern Europe – the so-called countries in

transition. And in the third world there was an increasing

awareness about the importance of these systems as a basis for

developing a modern and market oriented society. The FIG

Statement on the Cadastre, this way, established a standard. The

concepts were explained, settled, and made operational according

to the specific conditions in different parts of the world. |

|

The co-operation between FIG and the

UN-organizations was strongly intensified through the second

half of the 1990´s. The so-called Bogor Declaration is a good

example as a result of an interregional meeting of cadastral

experts held in Bogor, Indonesia, March 1996. The Bogor meeting

was based on a recommendation from the UNRCC-AP Conference in

Beijing in 1994. The meeting was also part of the efforts to

develop an active response to the problems of land management

and environmental protection as stipulated in Agenda 21 from

“The Earth Summit” in Brazil 1992. The cadastral systems were

hereby officially recognized for the first time as a core part

of the infrastructure supporting a sustainable environmental and

nature resource management. |

|

The Bathurst Conference was organized by FIG

Commission 7 and attracted 40 invited experts from 23 countries.

Half of the participants were surveyors from FIG, the other half

experts from other professions and representatives from UN

organizations such as UNDP, FAO, UN-HABITAT and the World Bank.

The Bathurst conference examined the major issues relevant to

strengthening land policies, institutions and infrastructures.

The resulting Bathurst Declaration on Land Tenure and Cadastral

Infrastructures for Sustainable Development established a

powerful link between good land administration and sustainable

development and provided a range of recommendations on how land

tenures and land administration infrastructures should evolve to

meet the challenges of upcoming 21st Century. |

|

The cadastral systems differ throughout the

world in terms of purpose, content and design and the technical

and economic effectiveness vary a lot. There was a need for a

vision for future cadastral systems to fulfil a multipurpose

role and in response to technology development. “Cadastre 2014”

presented such a vision in terms of six statements for

development of cadastral systems over the following years

towards 2014. The vision is based on a fully digital environment

and using privatisation and cost recovery as the core

organisational components. This publication of FIG Commission 7

has obtained remarkable international attention and established

a new agenda for discussing the cadastral issues. The

publication is translated into a range of foreign languages.

|

2.2 Cadastral Systems

In the Western cultures it would be hard to imagine a society without

having property rights as a basic driver for development and economic

growth. Property is not only an economic asset. Secure property rights

provide a sense of identity and belonging that goes far beyond and

underpins the values of democracy and human freedom. Historically,

however, land rights evolved to give incentives for maintaining soil

fertility, making land-related investments, and managing natural

resources sustainably.

Therefore, property rights are normally managed well in modern

economies. The main rights are ownership and long term leasehold. These

rights are typically managed through the cadastral/land registration

systems developed over centuries. Other rights such as easements and

mortgage are often included in the registration systems.

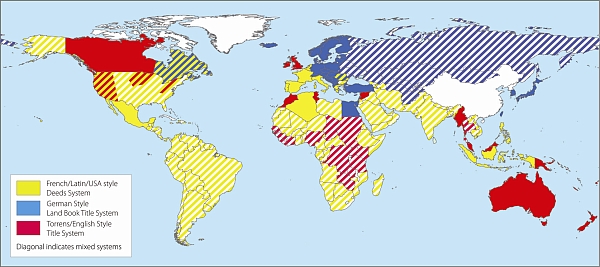

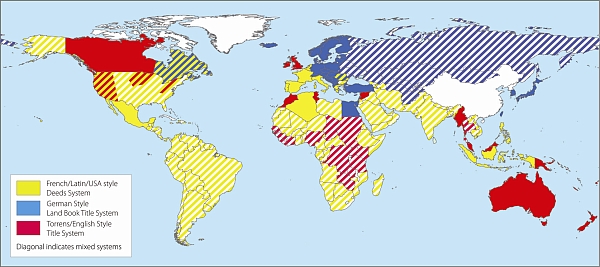

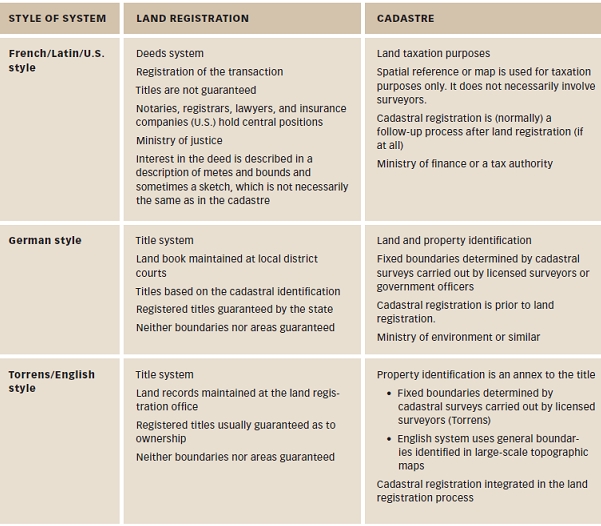

Cadastral Systems are organized in different ways throughout the

world, especially with regard to the Land Registration component (figure

2). Basically, two types of systems can be identified: the Deeds System

and the Title System. The differences between the two concepts relate to

the cultural development and judicial setting of the country. The key

difference is found in whether only the transaction is recorded (the

Deeds System) or the title itself is recorded and secured (the Title

System). The Deeds System is basically a register of owners focusing on

“who owns what” while the Title System is a register of properties

presenting “what is owned by whom”. The cultural and judicial aspects

relate to whether a country is based on Roman law (Deeds Systems) or

Germanic or common-Anglo law (Title Systems). This of course also

relates to the history of colonization.

Figure 2. World map of land registration systems (after Enemark

2004)

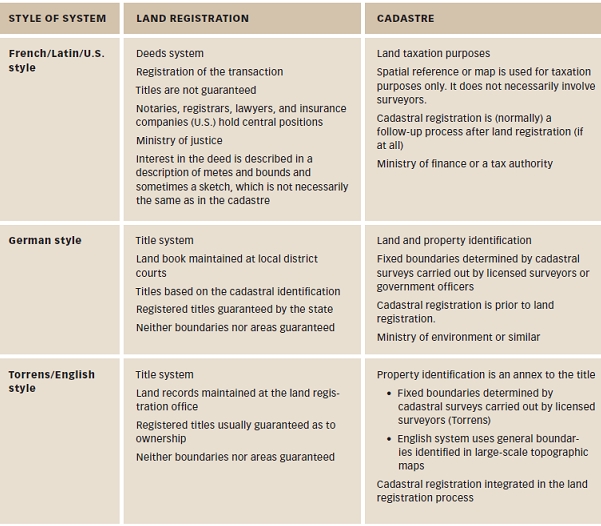

International experience suggests three basic approaches to cadastral

systems. These approaches are based on countries grouped according to

their similar background and legal contexts (German style,

Torrens/English approach, and French/Latin style). While each system has

its own unique characteristics, most cadastres can be grouped under one

of these three approaches. Just as there are three different styles of

land registration systems, these translate to three different roles that

the cadastre plays in each system. Again, while the role of the cadastre

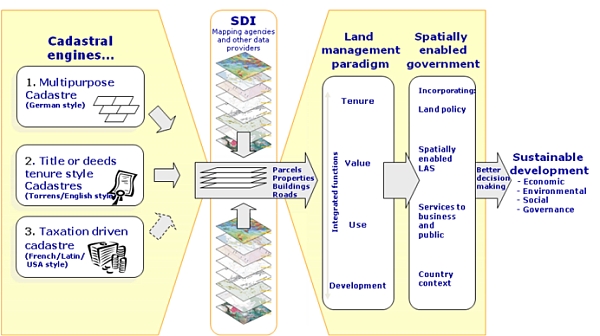

and the land registration styles are not definitive, figure 3 describes

the three approaches in general terms.

Figure 3. General relationships between land registries and

cadastres.

(Williamson, Enemark, Wallace, Rajabifard, 2010)

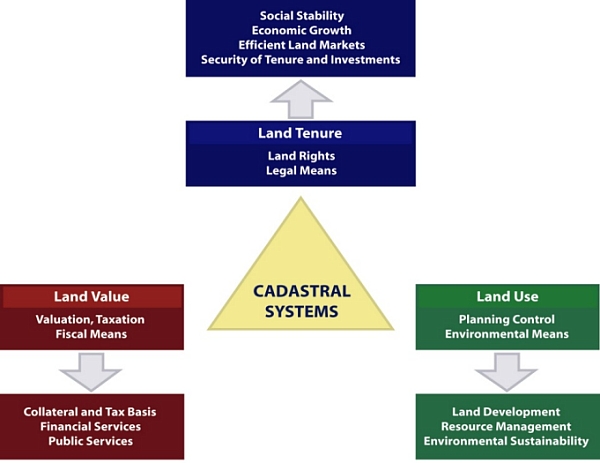

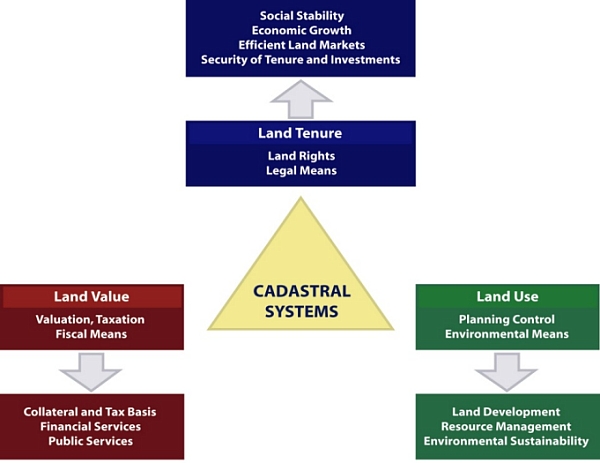

2.3 The Multipurpose Cadastre

Modern land administration theory acknowledges the history of the

cadastre as a central tool of government infrastructure and highlights

its central role in implementing the land management paradigm. However,

given the difficulty of finding a definition that suits every version it

makes sense to talk about cadastral systems rather than just cadastres

(figure 4). These systems incorporate both the identification of land

parcels and the registration of land rights. They support the valuation

and taxation of land and property, as well as the administration of

present and possible future uses of land. Multipurpose cadastral systems

support the four functions of land tenure, value, use, and development

to deliver sustainable development.

By around 2000, cadastral systems were seen as a multipurpose engine

of government operating best when they served and integrated

administrative functions in land tenure, value, use, and development and

focused on delivering sustainable land management. A mature multipurpose

cadastral system could even be considered a land administration system

in itself.

Figure 4: Cadastral systems provide a basic land information

infrastructure for running the interrelated systems within the areas of

Land Tenure, Land Value, and Land Use (Enemark, 2004).

2.4 Comparing and Improving Cadastral Systems

A website has been established

http://www.cadastraltemplate.org to compare cadastral systems on a

worldwide basis. About 42 countries are currently included (August 2010)

and the number is still increasing. The web site is established by

Working Group 3 (Cadastre) of the PCGI-AP (Permanent Committee on GIS

Infrastructure for Asia and the Pacific). The cadastral template is

basically a standard form to be completed by cadastral organizations

presenting their national cadastral system. The aim is to understand the

role that a cadastre plays in a state or a National Spatial Data

Infrastructure (NSDI), and to compare best practice as a basis for

improving cadastres as a key component of NSDIs. The project is carried

out in collaboration with FIG Commission 7 (Cadastre and Land

Management), which has extensive experience in comparative cadastral

studies. (Steudler, et.al. 2004).

It is generally accepted, however, that a good property system is a

system where people in general can participate in the land market having

a widespread ownership where everybody can make transactions and have

access to registration. The infrastructure supporting transactions must

be simple, fast, cheap, reliable, and free of corruption. It is

estimated that only 25-30 countries in the world apply to these

criteria.

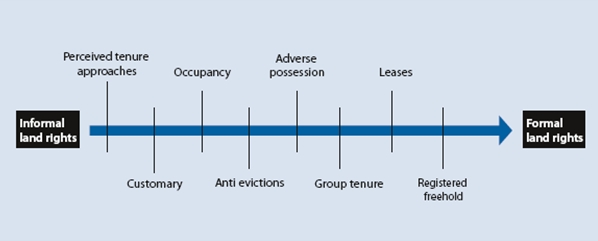

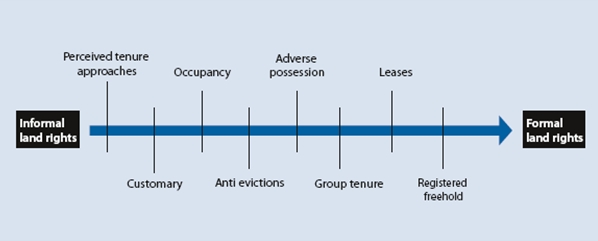

2.5 Limitations of formal cadastral systems

It is recognized that these legal or formal systems do not serve the

millions of people whose tenures are predominantly social rather than

legal. “Rights such as freehold and registered leasehold, and the

conventional cadastral and land registration systems, and the way they

are presently structured, cannot supply security of tenure to the vast

majority of the low income groups and/or deal quickly enough with the

scale of urban problems. Innovative approaches need to be developed”

(UN- HABITAT 2003). This should include a “scaling up approach” that

include a range of steps from informal to more formalised land rights.

This process does not mean that the all societies will necessarily

develop into freehold tenure systems. Figure 5 shows a continuum of land

rights where each step in the process can be formalised, with registered

freeholds offering a stronger protection, than at earlier stages.

Figure 5. Continuum of land rights (UN-Habitat, 2008).

Most developing countries have less than 30 per cent cadastral

coverage. This means that over 70 per cent of the land in many countries

is generally outside the land register. This has caused enormous

problems for example in cities, where over one billion people live in

slums without proper water, sanitation, community facilities, security

of tenure or quality of life. This has also caused problems for

countries with regard to food security and rural land management issues.

The security of tenure of people in these areas relies on forms of

tenure different from individual freehold. Most off register rights and

claims are based on social tenures. The Global Land Tool Network (GLTN),

facilitated by UN-HABITAT is a coalition of international partners (such

as FIG) who has taken up this challenge and is supporting the

development of pro-poor land management tools, to address the technical

gaps associated with unregistered land, the upgrading of slums, and

urban and rural land management. GLTN partners support a continuum of

land rights (figure 5), which include documented as well as undocumented

land rights, from individuals and groups, and in slums which are legal

as well as illegal and informal.

This range of rights generally cannot be described relative to a

parcel, and therefore new forms of spatial units are needed. A model has

been developed to accommodate these social tenures, termed the Social

Tenure Domain Model (STDM). A first prototype of STDM is available. This

is a pro-poor land information management system that can be used to

support the land administration of the poor in urban and rural areas,

which can also be linked to the cadastral system in order that all

information can be integrated.

The need for a complete coverage of all land by Land Administration

Systems is urgent. Not only for the registration of formal rights and

for the recordation of informal and customary rights. Also for managing

the value, the use of land and land development plans. This relates to

the global land administration perspective presented in Figure 6 below.

Complete coverage of all land in a Land Administration System is only

possible with an extendable and flexible model such as STDM that enables

inclusion of all land and all people within the four land administration

functions. So STDM will close part of the technical gap in developing

countries in terms of making Land Administration cover the total

territory.

|

The FIG Working Group 7.1 of Commission 7 on

Cadastre and Land Management took the lead from 2002 onwards, in

the development of the STDM in close co-operation with

UN-HABITAT. ITC, financially supported by the GLTN, developed a

first prototype of STDM that is supported by the World Bank. The

FIG Publication 52 presents the need for STDM, the properties of

STDM as a tool, and the benefit and use of STDM as a key means

of meeting the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Land tenure

types, which are not based on formal cadastral parcels and which

are not registered, require new forms of land administration

systems. STDM is a pro-poor land tool aiming to include informal

land rights into flexible, unconventional systems of land

administration that eventually can be incorporated into more

formal systems. |

3. LAND ADMINISTRATION SYSTEMS

When countries in Eastern and Central Europe changed from command

economies to market economies in the early 1990s, the UN Economic

Commission for Europe (UNECE) saw the need to establish the Meeting of

Officials on Land Administration (MOLA). In 1996, MOLA produced Land

Administration Guidelines (UN-ECE 1996) as one of its many initiatives.

In 1999, MOLA became the UN-ECE Working Party on Land Administration

(WPLA).

|

The UN-ECE Guidelines on Land Administration

was sensitive to there being too many strongly hold views in

Europe of what constituted a cadastre. Another term was needed

to describe these land-related activities. It was recognized

that any initiatives that primarily focused on improving the

operation of land markets had to take a broader perspective to

include planning or land use as well as land tax and valuation

issues. As a result, the publication replaced “cadastre” with

the term “land administration”. Widening the concept of a

cadastre to include land administration reflected its variety of

uses throughout the world and established a globally inclusive

framework for the discipline. An updated version of the

guidelines was published in 2005: “Land administration in the

UNECE region: Development trends and main principles”. |

For the first time, efforts to reform developing countries, to assist

countries in economic transition from a command to a market-driven

economy, and to help developed countries improve LAS could all be

approached from a single disciplinary standpoint, at least in theory.

That is, to manage land and resources “from a broad perspective rather

than to deal with the tenure, value, and use of land in isolation” (Dale

and McLaughlin 1999, preface).

Consolidation of land administration as a discipline in the 1990s

reflected the introduction of computers and their capacity to reorganize

land information. UN-ECE viewed land administration as referring to “the

processes of determining, recording, and disseminating information about

the ownership, value, and use of land, when implementing land management

policies” (UN-ECE 1996) The emphasis on information management

served to focus land administration systems on information for policy

makers, reflecting the computerization of land administration agencies

after the 1970s.

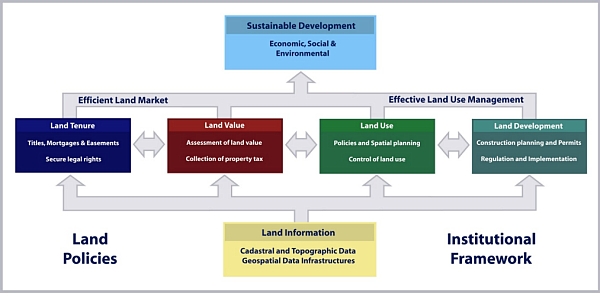

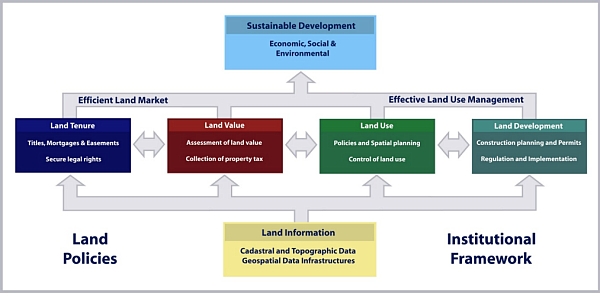

3.1 A global land management perspective

The focus on information remains but the need to address land

management issues systematically pushes the design of land

administration systems (LAS) toward an enabling infrastructure for

implementing land policies and land management strategies in support of

sustainable development. In simple terms, the information approach needs

to be replaced by a model capable of assisting design of new or

reorganized land administration systems to perform the broader and

integrated functions now required. Such a global perspective is

presented in figure 6 below.

Land management covers all activities associated with the management

of land and natural resources that are required to fulfil political and

social objectives and achieve sustainable development. The operational

component of the concept is the range of land administration functions

that include the areas of land tenure, land value; land use; and land

development.

Figure 6. A Global land management perspective (Enemark, 2004)

The four land administration functions (land tenure, land value, land

use, and land development) are different in their professional focus,

and are normally undertaken by a mix of professionals, including

surveyors, engineers, lawyers, valuers, land economists, planners, and

developers. Furthermore, the actual processes of land valuation and

taxation, as well as the actual land-use planning processes, are often

not considered part of land administration activities. However, even if

land administration is traditionally centred on cadastral activities in

relation to land tenure and land information management, modern land

administration systems designed as described in figure 6 deliver an

essential infrastructure and encourage integration of the four

functions:.

- Land Tenure: the allocation and security of rights in

lands; the legal surveys of boundaries; the transfer of property

through sale or lease; and the management and adjudication of

disputes regarding rights and boundaries.

- Land Value: the assessment of the value of land and

properties; the gathering of revenues through taxation; and the

management and adjudication of land valuation and taxation disputes.

- Land-Use: the control of land-use through adoption of

planning policies and land-use regulations at various government

levels; the enforcement of land-use regulations; and the management

and adjudication of conflicts regarding land-use and natural

resources.

- Land Development: the building of new infrastructure; the

implementation of construction planning; and the change of land-use

through planning permission and schemes for renewal and change of

existing land use

From this global perspective, land administration systems act within

adopted land policies that define the legal regulatory pattern for

dealing with land issues. They also act within an institutional

framework that imposes mandates and responsibilities on the various

agencies and organisations. LAS designed this way forms a backbone for

society and is essential for good governance because it delivers

detailed information and reliable administration of land from the basic

foundational level of individual land parcels to the national level of

policy implementation.

3.2 The FIG Agenda

FIG is strongly committed to the Millennium Development Goals and the

UN-Habitat agenda on the Global Land Tool Network. FIG should identify

their role in this process and spell out the areas where the global

surveying profession can make a significant contribution. Issues such as

tenure security, pro-poor land management, and good governance in land

administration are all key issues to be advocated in the process of

reaching the goals. Measures such as capacity assessment, institutional

development and human resource development are all key tools in this

regard. In pursuing this agenda FIG is working closely with the UN

agencies and the World Bank in merging our efforts of contributing to

the implementation of the MDGs. This provides a platform for focusing on

specific issues of mutual interest such as taking the land

administration agenda forward. At the same time it will contribute

further to the well founded cooperation between FIG and our UN partners.

In recent years FIG has established a number of relevant initiatives. A

rage of publications is presented below showing the impact of the FIG

agenda.

|

Following the Bathurst Declaration in 1999 a

number of FIG initiatives looked at addressing the goal of the

global agenda namely sustainable development. FIG published a

policy statement in 2001 on FIG Agenda 21 (FUG pub. 23) and a

report with guidelines on Women´s access to land with some key

principles for equitable gender inclusion in land administration

(FIG pub. 24). Sustainable development was also in focus in

the Nairobi Statement on Spatial Information for Sustainable

Development (FIG pub. 30) and the following best practice

guidelines on city-wide land information management (FIG pub.

31) both published as an outcome of 1st FIG regional conference

in Nairobi 2002.

The concept of organising regional conferences has proven to

be strong by bringing FIG to various regions in the world

especially developing countries and providing a unique

opportunity to address issues at the top of the regional and

local agenda. The resulting FIG publications include: The

Marrakech Declaration on Urban-Rural Development for Sustainable

Development (FIG pub. 33, 2004); The Costa Rica Declaration on

Pro-Poor Coastal Zone Management (FIG pub. 43, 2008); and the

Hanoi Declaration on Land Acquisition in Emerging Economies (FIG

pub. 51, 2010).

A pro-poor approach to land administration and management has

been addressing through the report on Informal Settlements – The

Road towards more Sustainable Places (FIG pub. 42, 2008) and the

comprehensive report on Improving Slum Conditions through

Innovative Financing (FIG pub. 44, 2008) produced as an outcome

of the joint FIG/UN-Habitat seminar during the FIG Working Week

in Stockholm, June 2008. The pro-poor approach has been further

addressed through development of the Social Tenure Domain Model

(FIG pub. 52, 2010) in cooperation with GLTN, UN-Habitat.

The big challenges on the global agenda such as climate

change, natural disasters, and rapid urban growth have been

addressed in The Contribution of the Surveying Profession to

Disaster Risk Management (FIG pub. 38, 2006) and the research

study on Rapid urbanisation and Mega Cities: The Need for

Spatial Information management (FIG pub. 48, 2010).

The overall challenge of Good Land Governance in support of

the global agenda has been analysed in cooperation with the

UN-agencies and the World Bank. Key outcomes have been the

Aguascalientes Statement on Development of Land Information

Policies in the Americas (FIG pub. 34, 2005) and the very recent

key publication on Land Governance in Support of the Millennium

Development Goals (FIG pub. 45, 2010) resulting from the joint

FIG/World Bank conference held in Washington, March 2009. Based

on this conference the World Bank has also published a joint

WB/FIG/GLTN/FAO publication “Innovations in Land Rights

Recognition, Administration and Governance”. |

4. LAND GOVERNANCE

All countries have to deal with the management of land. They have to

deal with the four functions of land tenure, land value, land use, and

land development in some way or another. A country’s capacity may be

advanced and combine all the activities in one conceptual framework

supported by sophisticated ICT models. More likely, however, capacity

will involve very fragmented and basically analogue approaches.

Different countries will also put varying emphasis on each of the four

functions, depending on their cultural basis and level of economic

development.

Arguably sound land governance is the key to achieve sustainable

development and to support the global agenda set by adoption of the

Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Land governance is about the

policies, processes and institutions by which land, property and natural

resources are managed. Land governance covers all activities associated

with the management of land and natural resources that are required to

fulfil political and social objectives and achieve sustainable

development. This includes decisions on access to land, land rights,

land use, and land development.

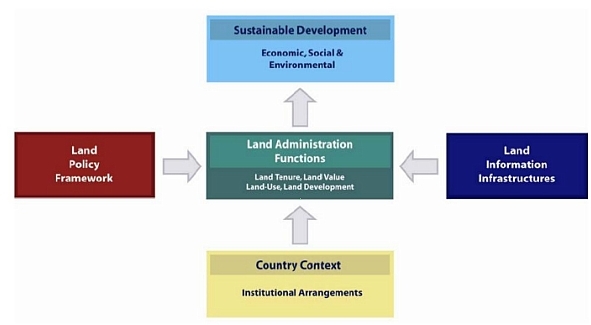

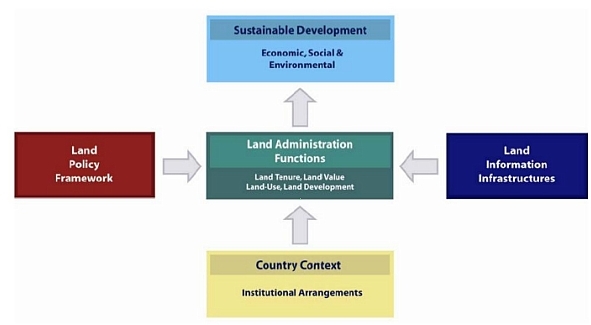

4.1 The Land management Paradigm

The cornerstone of modern land administration theory is the land

management paradigm in which land tenure, value, use and development are

considered holistically as essential and omnipresent functions performed

by organised societies. Within this paradigm, each country delivers its

land policy goals by using a variety of techniques and tools to manage

its land and resources. What is defined as land administration within

these management techniques and tools is specific to each jurisdiction,

but the core ingredients, cadastres or parcel maps and registration

systems, remain foundational. These ingredients are the focus of modern

land administration, but they are recognised as only part of a society’s

land management arrangements. The land management paradigm is

illustrated in figure 7 below.

Figure 7. The land management paradigm (Enemark, 2004)

The Land management paradigm allows everyone to understand the role

of the land administration functions (land tenure, land value, land use,

and land development) and how land administration institutions relate to

the historical circumstances of a country and its policy decisions.

Importantly, the paradigm provides a framework to facilitate the

processes of integrating new needs into traditionally organised systems

without disturbing the fundamental security these systems provide. While

sustainability goals are fairly loose, the paradigm insists that all the

core land administration functions are considered holistically, and not

as separate, stand-alone, exercises.

Land policy is simply the set of aims and objectives set by

governments for dealing with land issues. Land policy is part of the

national policy on promoting objectives such as economic development,

social justice and equity, and political stability. Land policies vary,

but in most countries they include poverty reduction, sustainable

agriculture, sustainable settlement, economic development, and equity

among various groups within the society.

Land management activities reflect drivers of globalization and

technology. These stimulate the establishment of multifunctional

information systems, incorporating diverse land rights, land use

regulations, and other useful data. A third driver, sustainable

development, stimulates demands for comprehensive information about

environmental, social, economic, and governance conditions in

combination with other land related data.

The operational component of the land management paradigm is the

range of land administration functions (land tenure, value, use and

development) that ensure proper management of rights, restrictions,

responsibilities and risks in relation to property, land and natural

resources.

Sound land management requires operational processes to implement

land policies in comprehensive and sustainable ways. Many countries,

however, tend to separate land tenure rights from land use

opportunities, undermining their capacity to link planning and land use

controls with land values and the operation of the land market. These

problems are often compounded by poor administrative and management

procedures that fail to deliver required services. Investment in new

technology will only go a small way towards solving a much deeper

problem: the failure to treat land and its resources as a coherent

whole.

|

The recent book Land Administration for

Sustainable Development (Williamson, Enemark, Wallace,

Rajabifard, 2010) explores the capacity of the systems that

administer the way people relate to land. A land administration

system provides a country with the infrastructure to implement

land policies and land management strategies. From the origin of

the cadastre in organising land rights to the increasing

importance of spatially enabled government in an ever changing

world, the book emphasises the need for strong geographic and

land information systems to better serve our world. |

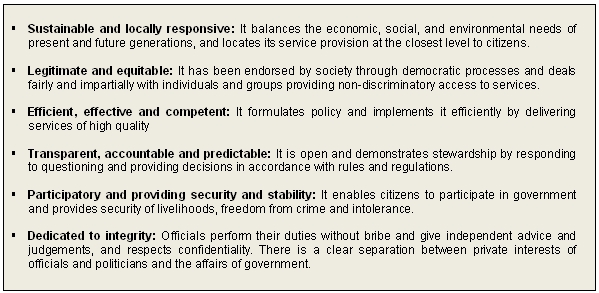

4.2 Good Governance

Governance refers to the manner in which power is exercised by

governments in managing a country’s social, economic, and spatial

recourses. It simply means: the process of decision-making and the

process by which decisions are implemented. This indicates that

government is just one of the actors in governance. The concept of

governance includes formal as well as informal actors involved in

decision-making and implementation of decisions made, and the formal and

informal structures that have been set in place to arrive at and

implement the decision. Good governance is a qualitative term or an

ideal which may be difficult to achieve. The term includes a number of

characteristics:

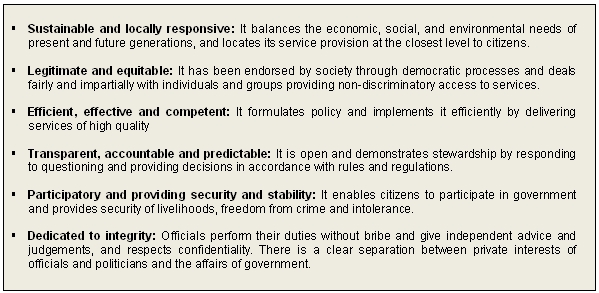

Figure 8. Characteristics of Good Governance (adapted from FAO,

2007)

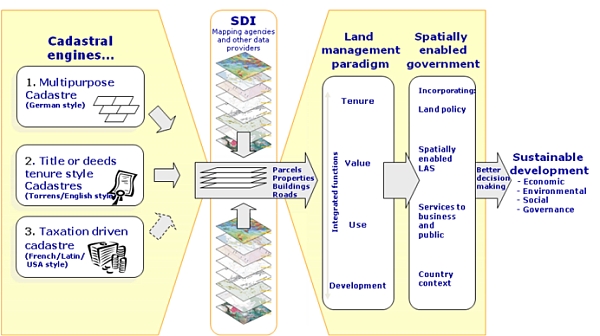

5. THE CADASTRE AS AN ENGINE OF LAS

The land management paradigm makes a national cadastre the engine of

the entire LAS, underpinning the country’s capacity to deliver

sustainable development. This is shown diagrammatically in figure 9. The

diagram highlights the usefulness of the large scale cadastral map as a

tool by exposing its power as the representation of the human scale of

land use and how people are connected to their land.

Wherever the cadastre sits in a national land administration system,

ideally it should assist the functions of land tenure, value, use, and

development. This way the cadastral system becomes the core technical

engine delivering the capacity to control and manage land through the

four land administration functions. They support business processes of

tenure and value, depending on how the cadastre is locally built. They

identify legal rights, where they are, the units that form the

commodities and the economy related to property. These cadastres are

much more than a layer of information in national SDI.

Figure 9. The cadastre as an engine of LAS - the “butterfly”

diagram

(Williamson, Enemark, Wallace, Rajabifard, 2010)

The diagram is a virtual butterfly: one wing represents the cadastral

processes, and the other the outcome of using the processes to implement

the land management paradigm. Once the cadastral data (cadastral or

legal parcels, properties, parcel identifiers, buildings, legal roads,

etc.) are integrated within the SDI, the full multipurpose benefit of

the LAS, so essential for sustainability, can be achieved.

The body of the butterfly is the SDI, with the core cadastral

information sets acting as the connecting mechanism. This additional

feature of cadastral information is an additional role, adding to the

traditional multipurpose of servicing the four functions. This new

purpose takes the importance of cadastral information beyond the land

administration framework by enlarging its capacity to service other

essential functions of government, including emergency management,

economic management, effective administration, community services, and

many more functions.

The diagram demonstrates that the cadastral information layer cannot

be replaced by a different spatial information layer derived from

geographic information systems (GIS). The unique cadastral capacity is

to identify a parcel of land both on the ground and in the system in

terms that all stakeholders can relate to, typically an address plus a

systematically generated identifier (given addresses are often

duplicated or are otherwise imprecise). The core cadastral information

of parcels, properties and buildings, and in many cases legal roads,

thus becomes the core of SDI information, feeding into utility

infrastructure, hydrological, vegetation, topographical, images, and

dozens of other datasets.

5.1 Spatially enabled society

Place matters! Everything happens somewhere. If we can understand

more about the nature of “place” where things happen, and the impact on

the people and assets on that location, we can plan better, manage risk

better, and use our resources better (Communities and Local Government,

2008). Spatially enabled government is achieved when governments use

place as the key means of organising their activities in addition to

information, and when location and spatial information are available to

citizens and businesses to encourage creativity.

New distribution concepts such as Google Earth provide user friendly

information in a very accessible way. Consider the option where spatial

data from such concepts are merged with built and natural environment

data. This unleashes the power of both technologies in relation to

emergency response, taxation assessment, environmental monitoring and

conservation, economic planning and assessment, social services

planning, infrastructure planning, etc. This also include design and

implementation of a suitable service oriented IT-architecture for

organising spatial information that can improve the communication

between administrative systems and also establish more reliable data

based on the use of the original data instead of copies.

The technical core of Spatially Enabling Government is the spatially

enabled cadastre. “Spatially enabled society is about managing

information spatially – not managing spatial information” (Williamson,

2010).

6. THE GLOBAL AGENDA

The eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) form a blueprint agreed

to by all the world’s countries and the world’s leading development

institutions. The first seven goals are mutually reinforcing and are

directed at reducing poverty in all its forms. The last goal - global

partnership for development - is about the means to achieve the first

seven. These goals are now placed at the heart of the global agenda. To

track the progress in achieving the MDGs a framework of targets and

indicators is developed. This framework includes 18 targets and 48

indicators enabling the on-going monitoring of the progress that is

reported on annually (UN, 2000).

Figure 10. The Eight Millennium Development Goals

The MDGs represent a wider concept or a vision for the future, where

the contribution of the global surveying community is central and vital.

This relates to the areas of providing the relevant geographic

information in terms of mapping and databases of the built and natural

environment, and also providing secure tenure systems, systems for land

valuation, land use management and land development. These aspects are

all key components within the MDGs.

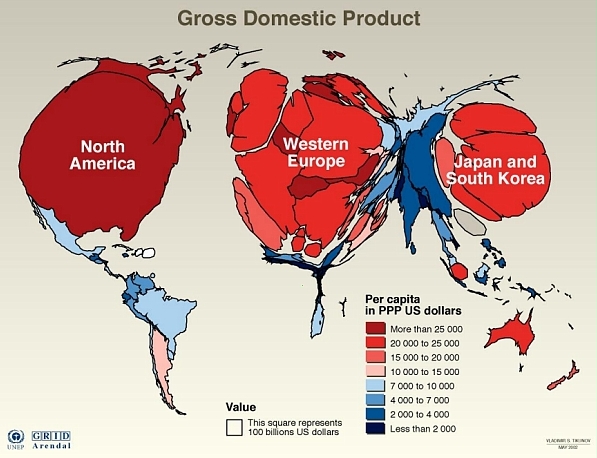

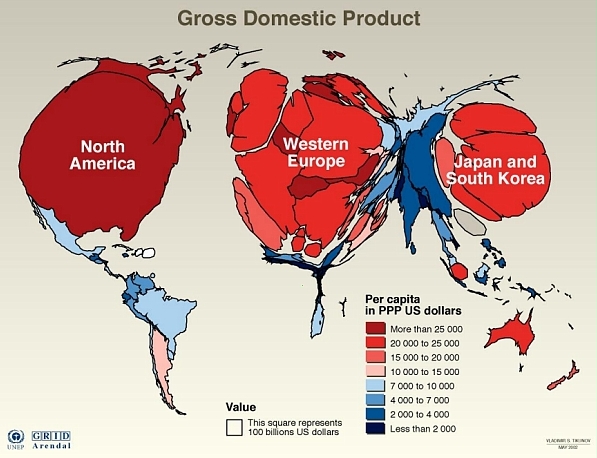

The global challenge can be displayed through a map of the world

(figure 11) where the territory size shows the proportion of worldwide

wealth based on the Gross Domestic Product. In surveying terms, the real

challenge of the global agenda is about bringing this map back to scale.

Figure 11. Map of the world where the territory size is shown

based on the Gross Domestic Product.

(Source: UNEP).

In a global perspective the areas of surveying and land

administration are basically about people, politics, and

places. It is about people in terms human rights,

engagement and dignity; it is about politics in terms of land

policies and good government; and it is about places in terms of

shelter, land and natural resources (Enemark, 2006).

Land administration is addressing societal needs. In Western cultures

it would be hard to imagine a society without having property rights as

a basic driver for development and economic growth. In most developing

countries, however, about 70% of the land is outside the formal land

administration system. Furthermore, land administration should also

address the key challenges of the new millennium such as climate change,

natural disasters, and rapid urban growth.

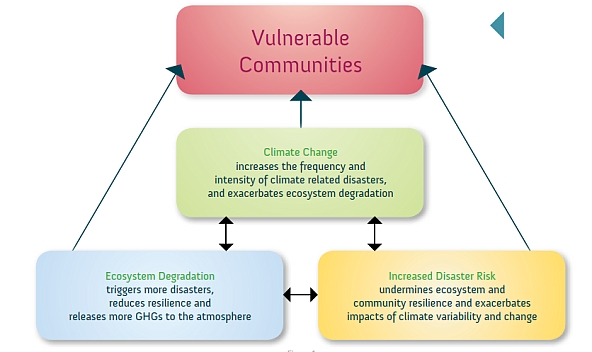

7. FACING THE NEW CHALLENGES

The key challenges of the new millennium are clearly listed already.

They relate to climate change; food shortage; urban growth;

environmental degradation; and natural disasters. These issues all

relate to governance and management of land. Land governance is a cross

cutting activity that will confront all traditional “silo-organised”

land administration systems. (Enemark, 2009).

The challenges of food shortage, environmental degradation and

natural disasters are to a large extent caused by the overarching

challenge of climate change, while the rapid urbanisation is a general

trend that in itself has a significant impact on climate change.

Measures for adaptation to climate change must be integrated into

strategies for poverty reduction to ensure sustainable development and

for meeting the MDGs.

Adaptation to and mitigation of climate change, by their very nature,

challenge governments and professionals in the fields of land use, land

management, land reform, land tenure and land administration to

incorporate climate change issues into their land policies, land policy

instruments and facilitating land tools.

More generally, sustainable land administration systems should serve

as a basis for climate change adaptation and mitigation as well

prevention and management natural disasters. The management of natural

disasters resulting from climate change can also be enhanced through

building and maintenance of appropriate land administration systems.

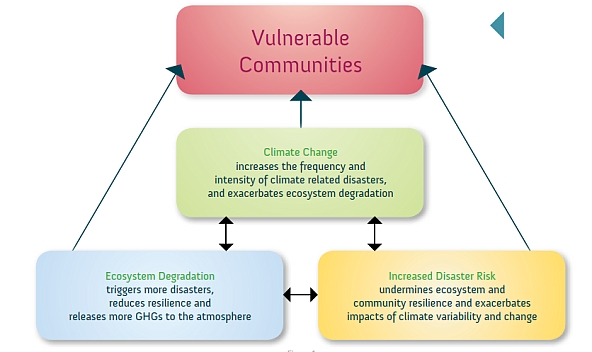

Climate change increases the risks of climate-related disasters, which

cause the loss of lives and livelihoods, and weaken the resilience of

vulnerable ecosystems and societies.

Figure 12. The interaction between climate change, ecosystem

degradation and disaster risk

(Source: UNEP, 2009)

Adaptation to climate change can be achieved to a large extent

through building sustainable and spatially enabled land administration

systems. This should enable control of access to land as well as control

of the use of land. Such integrated land administration systems should

include the perspective of possible future climate change and any

consequent natural disasters. The systems should identify all prone

areas subject to sea-level rise, drought, flooding, fires, etc. as well

as measures and regulations to prevent the impact of predicted climate

change.

Key policy issues to be addressed should relate to protecting the

citizens by avoiding concentration of population in vulnerable areas and

improving resilience of existing ecosystems to cope with the impact of

future climate change. Building codes may be essential in some areas to

avoid damage e.g. in relation to flooding and earthquakes. Issues may

also relate to plans for replacement existing settlements as an answer

to climate change impacts.

The measures of building integrated and spatially enabled land

information systems does not necessarily relate to the inequity between

the developed and less developed countries. Implementation of such

systems will benefit all countries throughout the globe. Therefore, the

integrated land administration systems should, in addition to

appropriate registration of land tenure and cadastral geometry, include

additional information that is required about environmental rating of

buildings, energy use, and current and potential land use related to

carbon stock potential and greenhouse gases emissions.

This also relates to the fact that climate change is not a

geographical local problem that can be solved by local or regional

efforts alone. To address climate change, international efforts must

integrate with local, national, and regional abilities.

Urbanisation is another major change that is taking place globally.

The urban global tipping point was reached in 2007 when over half of the

world’s population was living in urban areas; around 3.3 billion people.

This incredibly rapid growth of megacities (more than 10 million

inhabitants) causes severe ecological, economic and social problems. It

is increasingly difficult to manage this growth in a sustainable way. It

is recognised that over 70% of the growth currently happens outside of

the formal planning process and that 30% of urban populations in

developing countries living in slums or informal settlements, i.e. where

vacant state-owned or private land is occupied illegally and used for

illegal slum housing. In sub-Saharan Africa, 90% of all new urban

settlements are taking the form of slums. These are especially

vulnerable to climate change impacts as they are usually built on

hazardous sites in high-risk locations. Even in developed countries

unplanned or informal urban development is a major issue (FIG/WB 2010).

Urbanisation is also having a very significant impact on climate

change. The 20 largest cities consume 80% of the world’s energy use and

urban areas generate 80% of greenhouse gas emissions world-wide. Cities

are where climate change measures will either succeed or fail.

Rapid urbanisation is setting the greatest test for Land

Professionals in the application of land governance to support and

achieve the MDGs. The challenge is to deal with the social, economic and

environment consequences of this development through more effective and

comprehensive spatial and urban planning, resolving issues such as the

resulting climate change, insecurity, energy scarcity, environmental

pollution, infrastructure chaos and extreme poverty.

In conclusion, the linkage between urban growth, climate change

adaptation, and sustainable development should be self-evident. Measures

to manage urban growth and for adaptation to climate change will need to

be integrated into strategies for poverty reduction to ensure

sustainable development. The land management perspective and the role of

the operational component of land administration systems therefore need

high-level political support and recognition.

8. THE ROLE OF LAND PROFESSIONALS AND FIG

The role surveyors are changing. In a global perspective there is a

big swing that could be entitled “From Measurement to Management”. This

does not imply that measurement is no longer a relevant discipline to

surveying. The change is mainly in response to technology development.

Collection of data is now easier, while assessment, interpretation and

management of data still require highly skilled professionals. The role

is changing into managing the measurements. There is wisdom in the

saying that “All good coordination begins with good coordinates” and the

surveyors are the key providers.

The concept of a modern Positioning Infrastructure (combining

satellites and reference stations on the ground) still supports the

activities traditionally associated with a geodetic datum but extends

toward much broader roles on the global scale. It can be argued that

GNSS could be considered one of the only true global infrastructures in

that the base level of quality and accessibility is constant across the

globe (Higgins, 2009). Such a Positioning Infrastructure moves the focus

from measurement of framework points to management of the data received

from the positioning system.

The change from measurement to management also means that surveyors

increasingly contribute to building sustainable societies as experts in

managing land and properties. The surveyors play a key role in

supporting an efficient land market and also effective land-use

management. These functions underpin development and innovation for

social justice, economic growth, and environmental sustainability. The

big swing is implies a change from land surveyors to land professionals.

FIG is an UN recognised NGO representing the surveying profession in

about 100 countries throughout the world. FIG has adopted an overall

theme for the current period of office (2007-2010) entitled “Building

the Capacity”. This theme applies to the need for capacity building in

developing countries to meet the challenges of fighting poverty and

developing a basis for a sustainable future, and, at the same time,

capacity is needed in developed countries to meet the challenges of the

future in terms of institutional and organisational development in the

areas of surveying and land administration.

In general, FIG will strive to enhance the global standing of the

profession through both education and practice, increase political

relations both at national and international level, help eradicating

poverty, promote democratisation, and facilitate economic, social and

environmental sustainability. FIG can facilitate support of capacity

development in three ways:

- Professional development: FIG provides a global forum for

discussion and exchange of experiences and new developments between

member countries and between individual professionals in the broad

areas of surveying and mapping, spatial information management, and

land management. This relates to the FIG annual conferences, the FIG

regional conferences, and the work of the ten technical commissions

within their working groups and commission seminars. This global

forum offers opportunities to take part in the development of many

aspects of surveying practice and the various disciplines including

ethics, standards, education and training, and a whole range of

professional areas.

- Institutional development: FIG supports building the

capacity of national mapping and cadastral agencies, national

surveying associations and survey companies to meet the challenges

of the future. FIG also provides institutional support to individual

member countries or regions with regard to developing the basic

capacity in terms of educational programs and professional

organisations. The professional organisations must include the basic

mechanisms for professional development including standards, ethics

and professional code of conduct for serving the clients.

- Global development: FIG also provides a global forum for

institutional development through cooperation with international

NGO´s such as the United Nations Agencies (UNDP, UNEP, FAO,

HABITAT), the World Bank, and sister organisations (GSDI, IAG, ICA,

IHO, and ISPRS). The cooperation includes a whole range of

activities such as joint projects (e.g. The Bathurst Declaration,

The Aguascalientes Statement), and joint policy making e.g. through

round tables. This should lead to joint efforts of addressing

topical issues on the international political agenda, such as

reduction of poverty and enforcement of sustainable development.

FIG, this way, intends to play a strong role in improving the

capacity to design, build and manage surveying and land management

systems that incorporate sustainable land policies and efficient spatial

data infrastructures. These systems should also respond to the global

agenda in terms of the Millennium Development Goals and the new key

challenges in terms of climate change, natural disasters, and urban

growth.

9. FINAL REMARKS

Cadastral Systems underpin efficient management of the four key

functions within the land management paradigm. And the large scale

cadastral map is a key tool in providing the representation of the human

scale of land use and how people are connected to their land. The role

of cadastral systems has evolved over time from primarily serving as a

basis for land taxation and/or security of land tenure towards being the

key driver for achieving good governance of land and natural resources

in support of national policies and the global agenda.

Over the last decades FIG and the global surveying community has

taken a leading role in driving this evolution. Sound land governance is

the key to achieve sustainable development and to support the global

agenda set by adoption of the Millennium Development Goals.

FIG, this way, is building the capacity for taking the land policy

agenda forward in a partnership with the UN agencies and the World Bank.

This is documented in recent publications such as: “Land Governance in

Support of the Global Agenda” (FIG/WB, 2010) and “Innovations in Land

Rights Recognition, Administration and Governance” (WB/GLTN/FIG/FAO

(2010).

REFERENCES

Communities and Local Government (2008): Place matters: the Location

Strategy for the United Kingdom.

http://www.communities.gov.uk/publications/communities/locationstrategy

De Soto, H. (1993): The Missing Ingredient. The Economist, September

1993, pp. 8-10.

Enemark, S. (2004): Building Land Information Policies, Proceedings

of Special Forum on Building Land Information Policies in the Americas,

26-27 October 2004, Aguascalientes, Mexico.

http://www.fig.net/pub/mexico/papers_eng/ts2_enemark_eng.pdf

Enemark, S. (2006): People, Politics, and Places – responding to the

Millennium Development Goals. Proceedings of international conference on

Land Policies & legal Empowerment of the Poor. World Bank, Washington,

2-3- November 2006.

http://www.fig.net/council/enemark_papers/2006/wb_workshop_enemark_nov_2006_paper.pdf

Enemark, S. (2009): Spatial Enablement and the Response to Climate

Change and the Millennium Development Goals. Proceedings of the 18th UN

Regional Cartographic Conference for Asia and the Pacific, Bangkok,

26-30 October 2009.

http://unstats.un.org/unsd/METHODS/CARTOG/Asia_and_Pacific/18/18th-UNRCC-AP-Docs.htm

FAO (2007): Good Governance in Land Tenure and Administration, FAO

Land Tenure Series no 9. Rome.

ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/010/a1179e/a1179e00.pdf

FIG Publications, FIG Office, Copenhagen, Denmark.

http://www.fig.net/pub/figpub/index.htm

FIG/WB (2010): Land Governance in Support of the Millennium

Development Goals. FIG Publication no 45, FIG Office, Copenhagen.

http://www.fig.net/pub/figpub/pub45/figpub45.htm

Higgins, M. (2009): Positioning Infrastructures for sustainable Land

Governance. Proceedings of FIG/WB Conference on Land Governance in

Support of the MDGs, Washington, 9-10 March 2009.

http://www.fig.net/pub/fig_wb_2009/papers/sys/sys_1_higgins.pdf

Steudler, D., Williamson, I., Rajabifard, A., and Enemark, S. (2004):

The Cadastral Template Project. Proceedings of FIG Working Week 2004,

Athens, 22-27 May. 15 p.

http://www.fig.net/pub/athens/papers/ts01/ts01_2_steudler_et_al.pdf

United Nations (2000): United Nations Millennium Declaration.

Millennium Summit, New York, 6-8 September 2000, New York.

http://www.un.org/millennium/declaration/ares552e.pdf

UN-ECE (1996): Land Administration Guidelines with Special Reference

to Countries in Transition, United Nations Economic Commission for

Europe ECE/HBP/96, New York and Geneva, 112p.

http://www.ica.coop/house/part-2-chapt4-ece-landadmin.pdf

UN-ECE (2005): Land Administration in the UNECE Region: Development

trends and main principles.

http://www.unece.org/env/documents/2005/wpla/ECE-HBP-140-e.pdf

UNEP (2009): The Role of Ecosystem management in Climate Change

Adaptation and Disaster Risk Reduction. Copenhagen Discussion Series.

http://www.unep.org/climatechange/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=rPyahT90aL4%3d&tabid=129&language=en-US

UN-HABITAT (2003): Handbook on Best practices, Security of Tenure and

Access to Land. ISBN: 92-1-131446-1. UN-Habitat, Nairobi.

http://www.unhabitat.org/pmss/getPage.asp?page=bookView&book=1587

UN-HABITAT (2008): Secure Land Rights for all. UN Habitat, Global

Land Tools Network.

http://www.gltn.net/en/e-library/land-rights-and-records/secure-land-rights-for-all/details.html

WB/GLTN/GLTN/FAO (2010): Innovations in Land Rights Recognition,

Administration and Governance”. World Bank, Washington D.C.

http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTARD/Resources/335807-1174581646324/InnovLandRightsRecog.pdf

Williamson, I. and L. Ting (1999): Cadastral Trends. Proceedings of

FIG Commission 7, FIG Working Week, Sun City, South Africa, June 1999,

pp. 1-19.

Williamson, I.P. (2010): Wrap-up keynote, GSDI World Conference,

Singapore, 19-22 October 2010.

http://www.gsdi.org/gsdiconf/gsdi12/slides/P5c.pdf

Williamson, I.P., Enemark, S., Wallace, J. and Rajabifard, A. (2010):

Land Administration for Sustainable Development. ESRI Press Academic,

Redlands, California. USA. 497 pages. ISBN 978-1-58948-041-4. For

information, see:

http://www.fig.net/news/news_shortstories.htm

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Stig Enemark is President of the International Federation of

Surveyors, FIG 2007-2010. He is Professor in Land Management and Problem

Based Learning at Aalborg University, Denmark, where he was Head of

School of Surveying and Planning 1991-2005. He is a well-known

international expert in the areas of land administration systems, land

management and spatial planning, and related educational and capacity

building issues. He has published widely in these areas and undertaken

consultancies for the World Bank and the European Union in a range of

countries in Asia, Eastern Europe, and Sub Saharan Africa.

CONTACTS

Prof. Stig Enemark

FIG President 2007-2010

Department of Development and Planning,

Aalborg University

11 Fibigerstrede

9220 Aalborg

DENMARK

Email: enemark@land.aau.dk

Website:

http://www.fig.net/council/president_enemark.htm

|