Article of the Month -

July 2013

|

Towards a Capasity Development Framework - For Land Policy in Africa

Solomon HAILE, Ombretta TEMPRA, Remy SIETCHPING,

UN-Habitat, Kenya

1) The article discusses the

Land Policy Initiative (LPI) and how relevant activities are planned and

implemented to think through and develop strategies and road maps that

will culminate into the development of a coherent, unified and cutting

edge Capacity Development Framework (CDF). LPI Capacity Development was

a sub theme at the Working Week 2013. The LPI was discussed at the

GLTN/Director General forum which were spread over 4 sessions during the

Working Week and furthermore there was a special session on Africa LPI

Capacity Development where Solomon Haile presented the proposed Africa

LPI Capacity Development initiative.

ABSTRACT

Capacity development is at the heart of the Land Policy Initiative

(LPI). The AU Declaration on Land Issues and Challenges in Africa urges

member states to “build adequate human, financial, technical capacities

to support land policy development and implementation.” Drawing on the

overarching guidance provided in the Declaration, the LPI Strategic Plan

and Roadmap provides impetus for action by making capacity development

one of its key objectives and aiming at “facilitating capacity

development and technical assistance at all levels in support of land

policy development and implementation in Africa.” Capacity development

also features in other strategic objectives of the LPI Strategic Plan

and Roadmap. Knowledge creation/documentation/dissemination as well as

advocacy and communication, which form other elements of the Strategic

Plan and Roadmap, have significant capacity development overtones.

Realizing the significance of Declaration, the LPI Secretariat and its

strategic partner, namely, UN-Habitat and the Global Land Tool Network

(GLTN) joined hands to plan and implement relevant activities to think

through and develop strategies and road maps that will culminate into

the development of a coherent, unified and cutting edge Capacity

Development Framework (CDF). The goal of the CDF is to provide support

to land policy processes and address priority land issues in Africa. The

activities undertaken thus far to realize this goal include an expert

group meeting, a Writeshop and a pilot good practice training which

allowed to begin to engage relevant stakeholders and put in pace the

building blocks that will eventually form the CDF.

The paper will therefore unpack the major elements of the emerging CDF

which is currently under peer review. It will highlight the thinking

underpinning the CDF by elaborating the ‘what’, ‘why’, ‘how’, etc of

capacity development in the context of land policy processes and

priority land issues in Africa. These will provide insight on important

attributes of the CDF such as processes of engagement, methodology and

its various components including what makes it different from what is

out there.

1. BACKGROUND

1.1 An overview of the Land Policy Initiative for Africa and its

Capacity Development Dimension

Launched in 2006, the Land Policy Initiative (LPI) is a joint

programme of unmatched scale and ambition designed by the African Union

Commission (AUC), the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa

(UNECA) and the African Development Bank (AfDB) to enable land play its

vital role in Africa’s transformation which includes robust

socio-economic development, peace and security, and environmental

sustainability. Between 2006 and 2009, the LPI, which has its

Secretariat at the UNECA, developed, through a participatory and

inclusive process, the Framework and Guidelines (F&G) on Land Policy in

Africa. In April 2009, the AU joint conference of Ministers in charge of

Agriculture, Land and Livestock endorsed the F&G. In July 2009, The

African Heads of State and Government, at the 13th ordinary session of

the Assembly, approved the Declaration on Land Issues and Challenges in

Africa, calling for the effective use of the F&G at national and

regional levels. In 2010, the LPI received the mandate from the AU to

use the F&G in support of national and regional land policy processes,

developing and implementing strategies and action plans. The LPI has

since developed a five year Strategic Plan and Roadmap which covers nine

focus areas including capacity development. These have by and large been

political processes that generated unprecedented consensus around a

common framework, and have clarified vision, mission and mandate of the

LPI.

At a more operational level, the LPI has over the last two years

conducted a number of activities in support of its capacity development

agenda: an initial exploration of capacity needs in the five African

regions making these a part of the LPI regional assessments and securing

the leadership of Regional Economic Commissions (RECs); preliminary

identification of learning centers that it can partner with; the conduct

of training events (in Namibia and in Senegal), and; hosting a

sensitization forum on the LPI capacity development agenda on the

margins of the World Bank Annual Land Conference in Washington DC in

April 2012 which generated an overwhelming interest and pledges of

support from major international stakeholders.

1.2 Enhanced partnership with the GLTN/UN-Habitat for Capacity

Development

The GLTN has worked with LPI for a number of years and helped the

development of the F&G. In 2011, the LPI asked the GLTN and one of its

key partners UN-Habitat to specifically lead the design and

implementation of the capacity development component of LPI’s Strategic

Plan and Roadmap. This was readily accepted not least because of the

longstanding and shared interest that the two partners espouse to reform

land systems in Africa through land policy processes. Apart from having

a network of more than 50 major global players, the GLTN/UN-Habitat have

extensive experience in providing technical support to land stakeholders

at national and local levels. It has a proven track record of

facilitating coordination between and among land institutions and

development partners, guiding research and documentation, and producing

manuals and training packages on topics deemed relevant to land sector

reforms and implementation. Key strengths that the partnership brings to

the fore include knowledge of land issues in Africa, a network of

notable international actors that enjoy considerable expertise,

experience and influence in land matters, a brand new capacity

development strategy that has emerged from years of practice, an array

of land tools developed through research and pilot testing.

1.3 The Long Walk towards the Capacity Development Framework: Some

Notes on Methodology

The LPI and the GLTN/UN-Habitat collaboration on capacity development

first took shape in the Expert Group Meeting (EGM) that took place on

the 27-28 June 2012 in Addis Ababa. This was a crucial step in terms of

engaging key stakeholders as well as identifying the elements of the

then “idea only” CDF. The land and capacity development professionals as

well as representatives of various interest groups reviewed the

methodology presented to the EGM through a Background Paper and CDF

Outline. They also agreed on the key principles and approaches to be

considered in the development of a multi-year and multi-phased strategic

framework and roadmap that will unleash capacities to formulate, revise

and implement land policies and address priority land issues. The

deliberations of the EGM refined and strengthened the Background Paper

and the CDF Outline.

This was followed by a Writeshop in November 2012 in Kenya which

assembled together a diverse group of African and international experts

from academia, civil society, government, and development partners. The

International Institute for Rural Reconstruction (IIRR), an

international NGO which pioneered the Writeshop Methodology, provided

the logistics and substantive guidance which included producing initial

chapters of the CDF by carefully selected lead and collaborating

authors, facilitating the public peer review the contributions in a

workshop setting, rewriting and critiquing them through iterative

processes up until satisfactory versions were produced, editing and

compiling the chapters into a coherent and internally consistent

document. The product that had been produced by a group of experts

through this methodology was released in December 2012 and is now

circulated for external peer review. The draft CDF is a work in

progress. As such, it will also be subject to a rigorous technical and

political validation processes later this year.

2. WHAT IS CAPACITY DEVELOPMENT FOR LAND POLICY IN AFRICA?

The simple and straightforward answer provided in the draft CDF to

this foundational question is the following and readers will note that

this is a highly packed description which goes far and beyond a simple

definition. “Capacity development as used in [the Capacity

Development Framework] refers to the continual and comprehensive

learning and change processes by which African governments,

organizations and people identify, strengthen, adapt, create and retain

the needed capacity for effective land policy development,

implementation and tracking for the resolution of priority land

challenges facing the continent. Taking a capacity development approach

is an essential and appropriate response to the learning needs and

mindset changes required in complex environments, and the vital area of

land is no exception. The concept of ‘capacity development’ is an

important advance on that of ‘capacity building’. The latter implies

starting at a point zero with the use of external expertise. Capacity

development, on the other hand, emphasizes the presence and importance

of ongoing internal processes in each relevant context. The aim of a

capacity development process for land policy in Africa is therefore to

support, facilitate, improve and develop processes on a sustained and

ongoing basis at continental, regional, national and sub-national

levels. This means that land capacity development extends beyond

training and development of individuals’ skills and knowledge of land

and related matters to include the management of change in land policy

and implementation.” Clearly, capacity development in the context of

LPI is about enabling land policy processes – land policy development,

implementation and progress tracking. Where necessary and appropriate,

it is also about overhauling existing land policies that may have proved

un-implementable. As well, it is about finding lasting solutions to

priority land issues. The priority land issues that the LPI has been

grappling with are issues that have emerged from continent-wide

assessments. These are also issues whose resolution could jumpstart land

reforms through land policies.

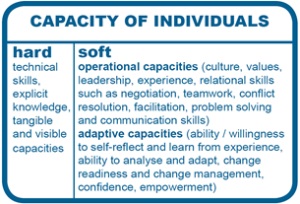

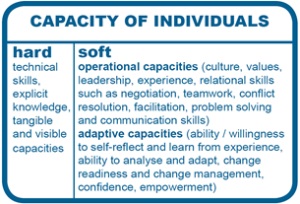

Another thinking that is embedded in the above description is the need

to develop capacities at all levels. This has two dimensions. The first

is the well-known and the now ubiquitous “individual, organizational

and societal level” dimension. The CDF will facilitate the

development of capacities and attainment of positive outcomes at all

levels. However, it will adjust its focus based on context specific

analysis of needs and opportunities. The second dimension that defines

the scope capacity development for land policy is the one that breaks

down the operational space into continental, regional, country and

local level needs and interventions. Let us zoom in one of these two

dimensions and further clarify the scope of capacity development for

land policy.

2.1 Capacities at all levels

The draft Framework realizes that capacity development is much more

than technical training. Unlike conventional capacity development, the

Framework appreciates that capacity development for land policy is

bigger than nurturing individuals’ skills and knowledge. This viewpoint

is in line with the emerging capacity development paradigm which defines

the concept itself as a “process whereby people, organizations and

society as a whole unleash, strengthen, create, adapt and maintain

capacity over time”.3)

In the emerging capacity development thinking, it is said that

developing the capacity of individuals (e.g. policy makers,

government officials, politicians, academics, technical professors,

community leaders, etc.) is likely to produce limited outcomes unless

the capacity of organizations (e.g. government departments, NGOs,

community based organizations, university departments, consultancy

firms, land institutes, etc.) witnesses a commensurate development and

change. Of course, there are exceptions to this. There are instances

when individuals with power, influence and a network can become powerful

change agents upon being sensitized to important public policy issues

and solutions through capacity development programs. If and when this

happens, there is a strong possibility to unleash the potential of large

groups change agents and institutions for reforms.

Equally, the outcome of capacity development at the organizational level

will remain below par if the overall enabling environment is

dysfunctional. Therefore, capacity at societal level, which

includes government institutions, ministries and ministerial

departments, institutions and organizations, civil society, professional

associations, private sector, etc and the rules, laws and policies that

regulate the interaction among these actors is vitally important, but

not easy to achieve. Land policy processes require work on all these

level albeit in varying intensities.

|

|

Figure1. Schematic Representation of Individual

Capacities4) and

Organizations’ Capacities5)

2.2 Principles

In an effort to clarify the nature of capacity development in the LPI

context, there a number of principles that have been specified in the

Background Paper as well as draft CDF. These include the following:

- Practicing capacity development as a process, not as a

stand-alone event. What this means in practice is that longer, more

rigorous and probably more costly engagements will be required to

make capacity development results.

- Making capacity development demand-driven, because supply

driven capacity development is often regarded as something ‘nice to

do, but not necessary.”

- Good land governance compliant: good land governance is

the sine qua non of a functioning land system including the policy

framework that provides strategic guidance to all laws, regulations,

land management and administration functions, processes and

procedures. Capacity development that fails to make a dent on weak

land governance will not succeed in achieving land policy goals.

- Promoting innovative, flexible and appropriate tool

development: land is one of the sectors where intractable issues

require tools or solutions. Capacity development needs to facilitate

this process of developing tools through for example action

learning. When it is done in a participatory way, tool development

itself is capacity development. Capacity development, in the context

of LPI, is thus tool development as well and the CDF will facilitate

this.

- Results-based: this kind of approach to capacity

development begins and ends with a focus on performance and results.

Intervention is justified on the basis of tangible evidence that

performance needs to be improved on very specific indicators. When

capacity development is result based, it also achieves strategic

goals and not specific project outputs.

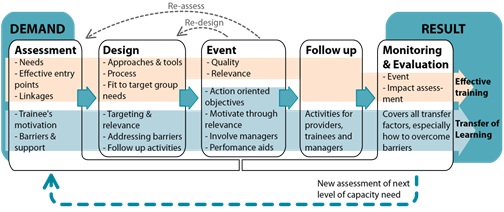

- Focusing on good practice training – Training is an

important component of the capacity development process and one that

is most frequently considered by program designers. However, the

draft CDF recognizes it is not a silver bullet that solves all

problems. Besides, if it is not well designed, it is likely to fail

as has been shown by numerous programs that development partners and

mainstream training providers have over the years implemented.

Hence, the draft CDF’s adherence to good practice training which is

described in section 4 and schematically presented in figure 2.

- Building on existing and ongoing initiatives – Capacity

development for land policy in Africa will capitalize on ongoing

initiatives and processes to learn what works and what does not

work, to create synergy and maximize coordination and efficiency.

This why the draft CDF is taking stock of existing initiatives and

partnerships.

- Combining ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ skills – the emphasis of

conventional capacity development on the so-called hard skills is

one of the challenges that has plagued the relevance land profession

for so long. In conventional formal training settings, land

professionals often learn things like land surveying, land law, land

economics, valuation, land information management, etc. They don’t

get to learn vitally important skills or knowledge related to gender

analysis, negotiations, communication, conflict resolution,

institutional analysis, community and participatory process, etc.

This crooked model is replicated in the practice arena and

additional capacity development initiatives of land professionals

continue to do the same thing that higher learning institutions do.

As a result, land systems struggle with professionals in leadership

and operational positions that are good at measurement, assessing

and determining property values using complex models, litigation,

etc, but do not understand and solve basic problems that communities

grapple with. Capacity development in the context of the LPI will

make a departure from this and attempt to strike the right balance

between hard and soft skills and knowledge by facilitating changes

in the way land professionals are trained – both in higher education

environment and in-service training settings.

- Appreciation of culture, diversity, context and existing

capacity - Each country, and sometimes areas within countries,

has its own values, mores, practices that must be taken into account

for capacity development to be appropriate and useful. Cultural

issues such as traditional relationships between different groups in

society and how they each relate to land are of critical importance.

Additionally it is essential to recognize and building on existing

capacities as a starting point for any intervention. In fact, this

is one of the attributes that distinguishes the thinking

underpinning capacity development as opposed to capacity building.

Importantly, this means understanding and working with local

knowledge, skills and expertise wherever they exist (e.g.

communities, governments, academic institutions, civil society

organizations, etc.). These are being accorded considerable

importance in the emerging CDF, because they contribute to making

capacity development home-grown and beneficiary-owned.

- Benchmarking land services provision: land policy process

at operational level aim to cut red tape and rot and usher is high

levels of transparency and accountability, efficiency, effectiveness

and excellence. Therefore, capacity development within LPI will be

about improving the standard of land service delivery taking into

account good practices and helping those lagging behind to aim for

higher performance metrics.

3. WHY A CAPACITY DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK FOR LAND POLICY?

3.1 The need to have a unified and comprehensive approach

In the process of refining the outline and the drafting of the

CDF, this was one of the questions that has repeatedly been raised

and responded to in many different ways. The one answer that came up

quite frequently during engagements with stakeholders is the need to

have a unified and comprehensive approach wherein shared principles,

methodologies, roles and responsibilities are to be clearly spelled

out. It is argued that such a framework will make the goals and

methodologies of developing capacities for land policy processes

across Africa a shared agenda in much the same way land stakeholders

in Africa are making the F&G and the Declaration on Land Issues and

Challenges a common strategic frameworks and joint reference points

to get the most out of limited resources. The CDF for Land Policy in

Africa aims to provide strategic and workable guidance to African

member states and other African land sector stakeholders in the

design, implementation and progress tracking of land policies at

continental, regional and national / local levels. The guidance will

include identifying and working on common capacity development

themes, processes, principles, approaches, etc that may be needed to

meet country or region specific requirements.

Like the F&G, the CDF will not impose a one-size-fits-all type of

capacity development approaches, principles and activities. The

diversity of existing capacities and the differences in capacity

needs at different levels across the continent are well recognized

and do not allow top-down program design and delivery. Still, there

are opportunities, challenges and risks that regions and countries

in Africa share with one another which lend themselves to a

well-designed comprehensive and unified framework. Finally, if one

considers the bigger picture, it is easy to note that this quest for

a common and unified framework is also part and parcel of the bigger

continental political agenda which aspires to bring people and

nations together through harmonization of policies, development of

supra-national infrastructure, promotion of trade and investment,

etc.

3.2 The need to optimize and coordinate resource use

If data about land and associated capacity land interventions in

Africa were carefully assembled and analyzed, it would be clear for

all to see the extent to which these interventions are piecemeal and

uncoordinated contributing to the duplication of activities and

misuse of precious human and financial resources, The Framework

therefore intends to facilitate coordination between and among

stakeholders with a view to minimizing duplication and maximizing

efficiency. By promoting peer-to-peer exchange, Africans with a

unified and shared capacity development vision can learn from and

build on each other strengths. On the strength of this coordination,

Africans and their development partners can expect to get better

value for money. Also, the Framework anticipates facilitating a

mechanism whereby novel thinking and innovations in capacity

development can easily be identified, adapted and used across

Africa.

3.3 A framework that enables solving common problems and

priority land issues

In addition to a lack of well thought-through land policies,

there are certain land issues that have emerged as key priorities of

most stakeholders in Africa. These are issues that stand in the

critical path of realizing the land resources potential of the

continent for poverty reduction and economic growth. Addressing

these issues within the framework of land policies (please note that

land policies are political instruments that can help bring about

comprehensive and meaningful reform) could jumpstart dysfunctional

land systems in many parts of Africa. This is thus one of the

rationales why the LPI needs a comprehensive and unified CDF. During

the preparation of the F&G for Land Policy in Africa, the Land

Policy Initiative (LPI) conducted five regional assessments – one

for each African region – through the Regional Economic Communities

(RECs). These included undertaking research, facilitating extensive

consultations and conducting validation workshops. It is through

these and similar engagements that the LPI has realized that some of

the priority issues that need to be mainstreamed in Africa’s land

policy thinking include women’s land rights, large scale land

based investment, land administration, land conflicts, customary

tenure and urban and peri-urban land issues.

In sum, it can be said that there is much value that can be added to

the land policy processes in Africa through a comprehensive

continental framework. The draft CDF succinctly outlines the

benefits like this: “A comprehensive approach would principally

entail a departure from the isolated, piecemeal approaches that have

characterized preceding efforts to develop capacities. Fragmented

approaches are often output-oriented rather than result-oriented. A

unified, comprehensive capacity development framework for land

policy that focuses on results has the potential to contribute to

sustainable land policies, as well as their implementation and

monitoring, by harnessing economies of scale….. A unified approach

also engenders coherence and synergy between the various activities

or countries involved. Such coherence is achieved through ongoing

exchange and feedback between participating entities, plugging the

gaps between technical and non-technical, rural and urban, or

stakeholders in development sectors. Finally, economies of scale are

realized through increased efficiencies (reduced transaction costs)

that result from a coordinated approach.”

4. HOW ARE CAPACITIES TO BE DEVELOPED?

The ‘how’ question of capacity development for land policy has

two dimensions: methodology and substance on the one hand and modus

operandi on the other hand. The latter refers to how different

stakeholders are to be engaged and assisted to contribute to the

attainment of required capacities in a specific context. It includes

things like working with and through partners. In relation to

training, for example, identifying and working with regional

learning centers is an important strategy. This entails supporting

selected training centers to grow in to “centers of excellence” in

regard to land policy processes. And they will then become focal

points for training in their respective regions including for

replicating training rolled out at continental level and expanding

outreach. On the methodology front, some of the things that are

being considered include action learning, needs assessment, good

practice training, etc and the way these link up with priority

matters like women land rights, customary tenure for example. Also,

the CDF is likely to move land stakeholders in Africa away from

training-only capacity development to the one that promotes

diversified approaches and tools (training plus or more than

training). The other capacity development approaches being

suggested include technical assistance, peer-to-peer exchange,

coaching and mentoring, experiential learning, and exposure visits.

Overall, there are very many different ways whereby capacities for

land policy processes can be developed. A strategic choice has to be

made based on 1) cutting edge thinking in the field 2) the needs of

the continent and its constituent parts 3) the innate requirements

of land policy processes. To illustrate, one may for example say

that capacity development for land policy should accentuate strong

sensitization and awareness raising exercises that enhance the

understanding of issues among policy makers and the formation of

social movements at the grassroots. Likewise, it can be said that

capacity development for land policy development should enhance

multi-disciplinary analysis, effective integration and harmonization

of the various facets of land (spatial, legal, economic, social,

cultural, and political). For land policy implementation, all that

capacity development needs to do is to strengthen organizations and

agencies, be they state, quasi-state, local, community or private.

These are all good and correct. But, such generic prescriptions will

not go far enough especially when dealing with complex capacity

development issues. Solving complex capacity issues and achieving

results require inclusive process, nuanced analysis and tools (‘how

to’ methods) that precisely determine what needs to be done and how

it should be done. This again brings to the fore the how question?

How are capacities to be developed? Engagements with the CDF

stakeholders have shown that capacities for land policies are to be

developed through:

4.1 Robust needs assessments

Of the many principles outlined in section 3, demand-driven

capacity development figures out prominently. Assessing needs or

gauging demand indeed is of utmost significance, for it allows

overcoming many of the failings of conventional capacity

development. In the context of land policy process, this doesn’t

mean sitting and waiting for the requests to come from various

stakeholders. It rather means going to the field (literally or

virtually), working with relevant actors to determine what needs to

be done and how to make land policy process move forward. A capacity

development that is anchored in strong needs assessment is the basis

for developing home-grown and country owned programs. It is also the

starting point to clarify SMART goals and achieve results. Needs

assessment is therefore one of the tools that inform how capacity

development for land policy processes must be designed and

implemented. Not only is this thinking embedded in the emerging CDF,

but also it is being taken further by analyzing good practices that

make needs assessment work better for land policy processes in

Africa. The quality of the capacity needs assessment has clearly

direct implications in the quality, and therefore the outcome, of

capacity development programmes. Specific areas of capacity need

should always be assessed – whenever possible through participatory

processes - within the framework of larger system-wide capacities

with a view to contributing to higher level goals that

underpin systemic, transformative and sustainable changes. Good

practice in capacity needs assessment6)

has the following attributes:

- Demand Driven Self-Assessments - The most informative

and accurate assessments are by local stakeholders, because they

have the most knowledge about the specific areas of need under

consideration and are also unlikely to let technical

considerations drive the assessment agenda.

- Starting with Existing Capacity - Identification of

existing capacity is the essential prerequisite for

understanding what individuals, organizations or sectors need to

move forward to the next level or stage of performance. Using a

‘gap analysis’ as the primary assessment tool does not help as

the goal is determining capacity gaps between current and

desired states of performance and bridging the same. This

analysis ignores the capacity that already exists, or the role

of important actors like key change agents and previous or

current processes on which new intervention should build.

Additionally, in the gap analysis approach the definition of

required capacity is often too ambitious, based on international

standards, rather than achievable next steps relevant to the

local context.

- Local Culture and Context - Analyzing culture and

context – at organizational, sector and institutional levels as

needed – is the only effective way to ensure that all enabling

and constraining factors are taken into account and understood.

In particular this means paying attention to cross cutting

issues, such as gender, power and the work environment.

Assessment tools should be adapted to take account of the fact

that the starting point of any intervention might be an urgent

need protect the capacity that already exists.

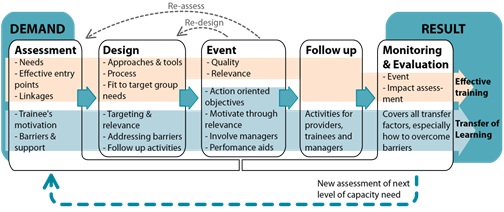

4.2 Good practice training

Increasing awareness of the limitations of conventional training

and of the fact that developing capacity in complex systems requires

a long-term strategic approach within which shorter initiatives can

be framed as stepping stones to longer term strategic goals. In line

with this thinking and drawing on UN-Habitat experience in training

and capacity development, an improved approach to training has

emerged. The capacity development strategy developed by the GLTN to

specifically address capacity gaps in the land sector says:

“Whether short or long-term in nature, all capacity development

initiatives work best if they are viewed as a process, not an event.

Such processes will always comprise some key components, namely:

assessment, design, the two parts of the delivery phase (event and

follow-up), and monitoring and evaluation, with iterative feedback

loops and impact assessment incorporated at a number of points (…)”.7)

The components of good practice training are:

- ASSESSMENT – This is about understanding what kind of

training is needed. It includes identifying the best entry

points, the motivation for participation in the training and

whether or not a system that supports training participants in

their backyard (in their organization or country) exists. The

quality of assessments is fundamental to the quality, and

therefore the results, of any capacity development initiative.

- DESIGN - Design is a series of decisions, the quality

of which is in direct relation to the quality of the information

the designers have from the assessment process about both

existing capacity and current change processes as well as the

capacity needs of the target group. Additionally, designers need

to be clear about the theories of capacity and change

they will apply to the design, especially with regard to issues

like the transfer of learning. The decisions to be made in the

design of capacity development initiatives come as answers to

three key questions: Who (group, organization or sector) needs

capacity? What do they need the capacity for? How can that

capacity best be developed and sustained?

- DELIVERY PHASE: THE EVENT - Delivery is the stage of

the capacity development initiative where the target groups and

providers come together. This can take different forms that may

be referred to generically as events. Annex 1 gives further

guidance on how to ensure high quality and effective delivery; a

key point is, of course, targeting the right participants.

- DELIVERY PHASE: FOLLOW-UP - Follow-up is essential

for the transfer of learning. There are many different types of

activities that support adequately learning. Managers or others

in the workplace can do some of them, while the training

providers and the participants themselves can do others. The

range includes, but is not limited to the following: workplace

coaching session; e-coaching support; peer coaching/support

groups; on-the-job training following the external event;

individual or group reflections using action learning tools;

application assignments with expert support available for

problem solving; return workshops for the exchange of experience

and learning from implementation; and, small grants to support

implementation of activities. The important point to reiterate

is that these activities must be considered as an integral part

of delivery, rather than as an optional add-on.

- MONITORING AND EVALUATION - While ways to define and

measure development results are generally clear, there are many

different ideas about how to define and measure capacity results

within specific contexts. Many land systems are

multi-dimensional, multi-level and multi-sectoral and capacity

development is a long-term process tied to a political agenda,

without a predictable, linear path. Although assessing results

can be complex and based on qualitative observations rather than

measurable indicators, it is nevertheless crucial to monitor the

results of capacity development processes, both for improving

the design of future processes and to adequately plan the

following steps of the ongoing processes.

- LEARNING MATERIALS - An important aspect of the good

practice training is the development of specific training and

learning materials and the adaptation – in terms of language,

culture, levels of complexity, case studies, etc. - of existing

learning materials to the specific audience.

At times, training design adopts the ‘training of trainers’

approach. This generally entails that a specific group of

participants are undergoing an additional learning process that

is expected to enable them to be ‘trainers’ in future learning

initiatives. A key consideration that the draft CDF is upholding

in this regard is that when designing a ‘training of trainers’

program, it is important to carefully select participants by

keeping in mind their capacity development responsibility in

their current assignments and roles. Importantly, the support

systems they have to replicate training and the extent to which

this support system is amenable to change are also crucial

considerations.

Figure 2. The Good Practice Training Cycle

Source: UN-Habitat Good Practice Note on Training

4.3 Fundamental changes in the curricula of formal training

providers

Formal education is arguably one of the most important ways of

developing capacities for the land sector. It includes education

programmes and institutions that provide training and capacity

development at certificate, diploma, under-graduate and

post-graduate degree levels. A capacity needs assessment for land

surveyors carried out in Francophone Africa8)

captured some of the gaps and needs for improvement in the education

of surveyors in the region. Similar findings came out of another

research entitled ‘Human9)

Capacity Needs Assessment and Training Program Development for the

Land Sector in in Kenya’.10)

In summary, it can be said that a large number of technical

education programmes in Africa are old fashioned, structured around

colonial models more fit to respond to the land sector needs of 20th

century Europe rather than the 21st century fast-changing and

rapidly urbanizing Africa.

Too few technical schools train small numbers of professionals at

high cost. This is one of the reasons for the ongoing shortage of

key professionals apart from being unsustainable. The knowledge

imparted often focuses on ‘hard’ skills only, while much needed

‘soft’ skills are neglected. It serves more the interest of

conventional land administration practices that have proven to be

too rigid and costly to service contemporary Africa. As a

consequence, this produces professionals who are poorly equipped to

face the reality of land challenges, but to entrench outdated,

expensive and elitist thinking. It hardly empowers to be creative

and devise affordable, flexible, pro-poor, gender responsive and

context specific home-grown land administration solutions.

There is therefore a need for a more innovative approach to capacity

development in the technical disciplines of the land profession.

Africa needs to have a larger pool of land professionals with

different levels of skills that can better respond to challenges on

the ground. It needs professionals whose knowledge and skills sets

meet requirements of its people. This does not always mean highly

trained university graduates. In some contexts, this could mean

creating a large cadre of paralegals and ‘barefoot’ surveyors. In

other contexts, this could mean people with specialized knowledge of

conveyancing, valuation, etc. A great deal of capacity issues in

many land offices could be met through technical and vocational

education and training. The CDF needs to inculcate this kind of mind

sets through its engagements with land training providers. Also, the

capacity of land practitioners, such as traditional and informal

land managers, community and grassroots members, should be

developed. New land administration tools, techniques and

technologies have to be incorporated into the learning processes.

The approach the CDF is likely to espouse will aim to change the way

land training is delivered on the continent and hope to “catch” the

future leaders and land professionals “young”, i.e. before

conventional systems corrupt their minds.

5. WHOSE CAPACITIES? AND BY WHOM?

In Africa, as is the case elsewhere in the world, the diversity

of land sector actors is immense and each represents different

roles, interests, capabilities and motivations. Each actor can

assume different roles at the different stages of land policy

processes (e.g. development, implementation, and monitoring).

This section broadly outlines the roles that different land and

non-land actors play in capacity development. The words ’broad

outline’ are key because the actors and stakeholders and the roles

with which they identify are context-specific. And these contexts

are too many and in some cases too specific to list and summarize

here. Each land sector stakeholder has multiple roles to play in

capacity development for land policy in Africa. These roles can be

referred to as capacity development beneficiary, capacity

development provider, and capacity development broker, but it is

important to keep in mind that most stakeholders have more than one

type of role. Also, it is important to note that each stakeholder

has and needs different types of capacities for different stages of

land policy (development, implementation, and progress tracking). To

breakdown and simplify a complex array of actors and roles, one of

the analytical frameworks being considered and used to map partners

and stakeholders, roles and responsibilities, etc is the following:

- Capacity developer / broker – country level

- Capacity development beneficiary – country level

- Capacity developer / broker – regional / continental level

- Capacity development beneficiary – regional / continental

level

The above framework, seemingly simple and straightforward, can

become complicated when a specific agenda that is relevant for a

particular context is identified and stakeholders want to action it.

Still, there are tools to analyze who does what. For the purpose of

this paper, the most important thing to note is that identifying

roles and responsibilities of various actors is as important as

having cutting edge tools and methodologies.

6. CONCLUSION

The paper has thus far tried to shed some light on issues and

themes underpinning the capacity development thinking within the LPI

framework. It has also highlighted the direction that the emerging

CDF is taking. The draft CDF is still very much a work in progress.

Therefore, it has not been possible to fully share what is in the

draft CDF. However, the material that has been presented in this

paper is more than adequate to share information, to solicit views

and feedback that will strengthen the CDF, and thereby help all

those interested in the agenda to contribute to the LPI vision,

mission and mandate.

As a way forward, it may be useful to take up a couple of themes

which the paper has alluded to, but has not fairly well dwelt on.

The first is partnership. Developing the capacity of African land

sector stakeholders to implement the Declaration on Land Issues and

Challenges in Africa and the F&G on Land Policy is a goal that

requires the joint effort of a large number of partners. The draft

CDF recognizes that a well-structured collaboration based on shared

values, complementarity, comparative advantage, is vitally important

and must be actively sought, strengthened and expanded. The CDF will

promote this and it is hoped that relevant actors on the continent

will embrace the CDF to leverage capacity development resources to

create low-cost, high-value programs. The collaboration can include

harmonizing and integrating capacity development opportunities

offered by existing initiatives, programs, institutions and

platforms. Obviously, such collaboration can only enhance coherence

among various initiatives and the relevance and credibility of all

those involved. Linkages among different land initiatives, including

capacity development activities is in the best interest of all

actors as it enables them to avoid conflicting messages and overlaps

and waste in scarce financial and human resources. The CDF can, when

completed, be a platform that provides opportunities to promote the

coming together of all actors to maximize relevance and results. The

extent to which partners will be committed to work together under

the emerging CDF will determine whether or not these goals will be

achieved.

The second is about resources. Africa counts on a range of partners

to support the implementation of the CDF. Continental and regional

bodies, national and local authorities, national and international

NGOs, training and research institutions, traditional leaders,

community-based organizations, professional associations, private

sector, and bilateral and multilateral development partners have all

an important role to play and are called upon to embrace the LPI and

its CDF in this spirit.

Land policy development is a lengthy process. It is therefore not

cheap. As well, it should not be done ‘on the cheap’ especially if

this means compromising inclusiveness and consultative processes.

Land policy implementation is even more costly. These costs should

be assessed well in advance in the policy reform and design stage.

The same could be said about capacity development for land policy.

Resources to jumpstart and sustain it should be estimated and

catered for early in the process to ensure a degree of preparedness

and prevent capacity constraints from standing in the way of policy

development and implementation. In regard to resource allocation,

international development partners have a significant role to play.

But, external funding alone cannot and should not fully cater for

this. African governments should be prepared to be a primary source

of funding and finance land policy processes and the attendant

capacity development activities.

2) The paper draws from the CDF Background Paper and the draft

CDF. These are duly acknowledged where appropriate.

3) OECD (2006), “The Challenge of Capacity Development: Working

Towards Good Practice”, DAC Guidelines and Reference Series, OECD,

Paris. http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/4/36/36326495.pdf

4)Schematic representation reflecting the Core Concept section of

the LenCD Learning Package for Capacity Development, available at

www.lencd.org/group/learning-package

5) Schematic representation re-elaborated from the conceptual and

operational frameworks for institutional capacity development

developed by the UN-Habitat Training and Capacity Building Branch

(update / check / improve reference)

6) ‘UN-Habitat Good Practice Note: Training’, page 19

7) GLTN Capacity Development Strategy, draft document, June 2012,

following from e.g. OECD (2006). The Challenge of Capacity

Development: Working Towards Good Practice. OECD Publishing: Paris,

France. OECD (2006), “The Challenge of Capacity Development: Working

Towards Good Practice”, DAC Guidelines and Reference Series, OECD,

Paris.

http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/4/36/36326495.pdf

8) 'Séminaire d’évaluation des besoins en formation des géomètres en

Afrique subsaharienne’, 2012

9) The term human capacity is used in this assessment to make a

distinction between what people in organizations require and what

those organizations require in terms of hardware, facilities, etc.

10) Unpublished Report on ‘Human Capacity Development Needs

Assessment and Training Programme for the Land Sector in Kenya’ .

REFERENCES

- Africa Union Commission (AUC), Africa Development Bank

(AFdB), United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA),

2007, ‘Background document - Land Policy in Africa: a framework

to strengthen land rights, enhance productivity and secure

livelihoods, 2007

- AUC/AFDB/UNECA, 2009, ‘Framework and Guidelines on Land

Policy in Africa’, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- AUC, 2009, Declaration on Land Issues and Challenges in

Africa.

- Dossier sur l’État des Lieux de la Tenure Coutumière en

Afrique, 2012

- Global Land Tool Network (GLTN), 2012, Draft Capacity

Development Strategy, unpublished internal Document.

- Government of Kenya, Sida-Kenya, UN-Habitat, 2011, ‘Human

Capacity Development Needs Assessment and Training Programme for

the Land Sector in Kenya’, Unpublished Repprt, produced by Peter

M. Ngau, Jasper N. Mwenda, and Michael Mattingly, Nairobi,

Kenya, Coordinated by Solomon Abebe Haile.

- Learning Network on Capcity Development (LenCD)…..

http://www.lencd.org/group/learning-package/document/capacity-core-concept

- OECD, 2006, “The Challenge of Capacity Development: Working

Towards Good Practice”, DAC Guidelines and Reference Series,

OECD, Paris.

- ‘Séminaire d’évaluation des besoins en formation des

géomètres en Afrique subsaharienne; synthèse des réponses,

propositions et conclusions’, GLTN, UN-Habitat, FIG, et

Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie, 2010.

- UNECA, Framework for Tracking Progress in Land Policy

Formulation and Implementation in Africa, Final Draft (LPI)

- UN-Habitat, 2007, ‘How to develop a pro-poor land policy –

Process, Guide and Lessons’, 2007

- UN-Habitat, 2012, Good Practice Note: Training, Unpublished

Consultancy Report. The Nairobi Action Plan on Large Scale

Land-Based Investments in Africa, 2011

- The Draft Capacity Development Framework, 2012, Unpublished

and under review

- The Land Policy Initiative Strategic Plan and Roadmap,

Unpublished Internal Document

- The Nairobi Action Plan on Large Scale Land-Based

Investments in Africa, 2011

CONTACTS

Solomon Haile, Ph.D

Global Land Tool Network

Urban Legislation, Land and Governance Branch, UN-Habitat

P.O.Box 30030-00100

Nairobi, KENYA

Tel:+254207625152

E-mail:

Solomon.Haile@unhabitat.org

Ombretta Tempra

E-mail:

Ombretta.Tempra@unhabitat.org

Remy Sietchiping, PhD

United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat)

P.O. Box 30030

Nairobi 00100, KENYA

E-mail:

Remy.Sietchiping@unhabitat.org

|