Article of the Month - April 2021

|

Innovative Tools and Strategies to Conciliate

Floodplain Restoration Projects and Spatial Planning in France: the

“Over-Flooding Easement

Marie Fournier, Adèle Debray And Mathieu Bonnefond,

France

|

|

| Marie Fournier |

Mathieu Bonnefond |

This article in .pdf-format

(11 pages)

This paper is mainly based on the results of the FARMaine project.

The authors analyzes the consequences of environmental public

policies on agricultural land and practices in the Maine river basin

(Région Pays de la Loire).

SUMMARY

In France, flood management policies have strongly evolved since the

1990s. Flood mitigation has become a key strategy in order to contribute

to the diversification and sustainability of flood risk management

policies (Larrue et al., 2015).

In this context, more and more river authorities launch and implement

floodplain restoration and water retention projects locally in France.

Like in most Western European countries, it is now taken for granted

that flood management requires ‘‘making space’’ for water by increasing

retention capacity of floodplains (Warner et al., 2012). However, in

many European countries, floodplain restoration still proves to be a

societal challenge (Moss, Monstadt, 2008) and rural land has an

important role to play in flood mitigation (Morris et al., 2010).

In this context, our presentation focuses on a specific legal

mechanism – the over-flooding easement (“servitude de sur-inondation”) –

created in France in 2003 in order to facilitate the implementation of

floodplain restoration and water retention projects. Our research shows

that more and more river and flood management institutions choose to use

this public utility easement in order to control land uses and

activities in the floodplains and avoid land acquisition. However, this

legal tool may have important consequences for land uses and economic

activities. We use the case of the Oudon river basin (Western France,

(Mayenne/Maine-et-Loire)) and describe how river managers have

succeeded, via local agreements, in building synergies between their own

objectives (the restoration of floodplains and water retention areas)

and farming activities impacted by the over-flooding easement.

1. INTRODUCTION

In France, flood risk management (FRM) policies have strongly evolved

since the 1990s. Flood mitigation has become a key strategy in order to

contribute to their diversification and sustainability (Larrue et al.,

2015). Flood mitigation measures aim at reducing the likelihood and

magnitude of flooding; they are complementary to flood defense. They are

being put in place through actions that accommodate (rather than resist)

water, such as natural flood management or adapted housing (Fournier et

al., 2016). Within this strategy, more and more river authorities, i.e.

river syndicates or inter-municipalities competent for FRM, launch and

implement floodplain restoration and water retention projects in France.

Like in most Western European countries, it is now taken for granted

that flood management requires ‘‘making space’’ for water by increasing

the retention capacity of floodplains (Warner et al., 2012). However, in

many European countries, floodplain restoration still proves to be a

societal challenge (Moss, Monstadt, 2008) and rural land has an

important role to play in flood mitigation (Morris et al., 2010).

In this context, our presentation focuses on a specific legal

mechanism – the over-flooding easement (“servitude de sur-inondation”) –

created in France in 2003 in order to facilitate the implementation of

floodplain restoration and water retention projects. The over-flooding

easement was created in order to contribute to floodplain storage and

conveyance projects (identified as “making space for water” projects by

Morris et al., 2016). Thanks to this public utility easement, river

authorities can delineate and fix specific rules in water retention

areas which have been equipped with hydraulic works. Our research shows

that more and more river authorities choose to use this easement in

order to control land use in the floodplain and avoid land acquisition.

However, this legal tool may have important consequences for local land

users and economic activities. As a result, negotiation processes are

often launched in order to conciliate FRM objectives and other/former

land uses.

This presentation is mainly based on the results of the FARMaine

project (“Pour et Sur le Développement Régional” (PSDR4 Grand Ouest

2016-2020) Research Programme (www.psdrgo.org)).

This project analyzes the consequences of environmental public policies

on agricultural land and practices in the Maine river basin (Région Pays

de la Loire). In this presentation, we mainly use the results coming

from scientific and grey literature review, semi-structured interviews

with institutional local stakeholders on the Oudon river basin and

participant observation.

First we describe the national context in which the over-flooding

easement has become a key procedure for local authorities in their

projects to mitigate the flood risk. Then, we explain more in detail the

legal mechanisms for this new public utility easement. In particular, we

point out its advantages and limits for river managers. Eventually, we

use the example of the Oudon river basin and focus on the negotiation

processes and agreements which have been necessary for local authorities

and private stakeholders to build synergies between FRM policies and the

local economic activities impacted by the over-flooding easement.

2. A LEGAL INSTRUMENT AT THE DISPOSAL OF FRENCH LOCAL AUTHORITIES TO

FACILITATE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF MITIGATION PROJECTS

If the over-flooding easement was introduced in the French law about

20 years ago, it took some years before French local authorities start

to use this legal instrument. Empirical research (Broussard, 2019) shows

that more and more French local authorities competent for flood and

river management have preferred this instrument to others (such as land

acquisition) during the last five years. In order to understand its

increasing use, it is important to recall that it has been concomitant

to two major evolutions in French FRM policies.

First, it is only since a decade or so that local authorities play an

increasing role and involvement in FRM policies in France. While FRM

used to be mainly dominated by the French central government

administration, new competences have been transferred to them by law

during the last years. In particular, the MAPTAM law (2014) conferred

them a new responsibility for water management and flood prevention

(so-called GEMAPI competence (GEstion des Milieux Aquatiques et

Prévention des Inondations)). This new competence was created in order

to facilitate the integrated management of water and floods issues at

local level. Within the MAPTAM Act, municipalities are clearly

identified as the key stakeholder in flood risk management. They hold an

exclusive and mandatory competence in this field. Even though they were

already responsible by law for water production and delivery, the MAPTAM

Act defines several new competences for them:

- River basin management;

- Maintenance and works on rivers, canals, lakes;

- Defense against floods and sea;

Protection and restoration of rivers and wetlands.

In practice, it is mainly via inter-municipal organizations (river

syndicates or intercommunalities) that French local authorities launch

flood mitigation projects to better deal with natural hazards (Fournier,

2019)

In this context, French local authorities are progressively investing

the mitigation strategy within FRM policies. Among all FRM strategies

(defense, preparation, recovery, prevention and mitigation as defined by

Hegger et al., 2016), preparation, recovery and defense still remain

strongly dominated by the French central government, but the mitigation

strategy has been more and more invested by local authorities within the

last decade. Indeed, it has become an opportunity for them to challenge

and face the prevention rules imposed by central government in the Plans

for Flood Risk Prevention (Plans de Prévention des Risques inondation

(PPRi)), often considered as being too restrictive (Fournier et al.,

2016). Since a decade or so, French municipalities or intercommunalities

have started to launch mitigation projects addressing both hazard or

vulnerability issues. Measures at property level (flood resilient

housing) but also measures to better deal with natural hazards (flood

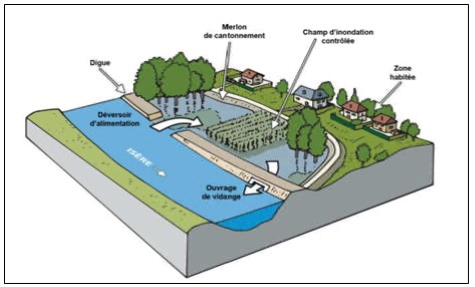

storage areas such as presented in Figure 1, sustainable urban drainage,

wetland creation or the restoration or river corridors) have been

launched. Financial incentives were also created by the central

government in order to promote mitigation projects at local level.

Figure 1 : schematic diagram of a flood

storage area

(source: Isère River Syndicate (symBHI))

To conclude, in a context of climate change and growing uncertainties

about natural hazards, French local authorities are entitled to define

new ways to deal with the flood risk. In this context, the over-flooding

easement has become more frequently used in the implementation of

mitigation projects dealing with the flood hazard. For French local

authorities, this easement constitutes an opportunity, with limited

financial investments, to improve local resiliency. As described in the

following section, without any land acquisition, the over-flooding

easement is implemented in order to control activities (and mainly

farming) in flood retention areas.

3. A LEGAL INSTRUMENT TO BETTER CONCILIATE FLOOD MITIGATION

OBJECTIVES AND CURRENT LAND USES

In this section, we describe more precisely the mechanisms of this

legal instrument. We also point out its advantages and limits for local

authorities.

As stated previously, the over-flooding public utility easement was

created in 2003 with two other public utility easements (creation or

restoration of mobility areas in the riverbed and protection or

restoration of strategic wetlands). They are defined in article L.211-12

article in the French Environment Code.

This legal procedure was designed in order to facilitate the protection

of temporary water storage areas. It is important to point out that the

“over-flooding” easement can only be implemented in an area where the

retention capacity has been increased by hydraulic works (via the

construction of dams, dikes and so on). Therefore, the objective is to

increase flooding and store water in the upper part of a riverain basin,

in order to reduce floods and water run-off downstream and in urban

areas.

Such projects may have important direct and indirect impacts on

agricultural/farming land (increase of the water level and duration of

submersion, extension of the flood prone area and so on… (Ministère de

l’Agriculture et de l’Alimentation/Ministère de la Transition Ecologique

et Solidaire, 2018)).

Both central government administration and local public authorities

may be at the initiative of this procedure but empirical research shows

that this is mainly done by the latter (Broussard, 2019). The

enforcement of this easement is quite complicated. First, a public

inquiry must be conducted locally. The project is described and

justified. A map of the area and the list of landowners must be settled.

Complementary inquiries may be needed if hydraulic facilities are

planned to increase water retention. Then, a decree taken by the local

representative of the central government, the prefect (Préfet),

identifies the perimeter and parcels concerned by the easement.

There are various consequences for landowners and tenants. The decree

may impose a preliminary declaration for any new hydraulic project that

could reduce or limit water retention in the future. Landowners and

tenants must also give permanent access to their land for the public

agents in charge of the maintenance of the water retention area. If the

central government administration or local authorities own and rent

agricultural land in the perimeter, they can impose binding clauses to

the tenants in order to prevent damages when leases are renewed. Some

compensations were created by the 2003 “Risks” Law. First, financial

compensations are paid by the procedure holder to landowners, when

prejudices are direct and certain. Tenants (mainly farmers) may also

receive financial compensations in case of damage on buildings (but not

always for crops or livestock losses). Landowners may also impose the

acquisition of their land by the procedure holder (“droit de

délaissement”). In 2003, the “Risks” Law also gave the possibility for

local authorities to use their pre-emptive right to buy land in the

perimeter of the easement (Struillou, 2012).

In a nutshell, river restoration and flood mitigation projects have

often proved to be conflictual along rivers in France and their holders

must define specific strategies to control land uses (Bonnefond et al.,

2017). This new procedure is an opportunity for local authorities to

avoid drastic land tenure measures, such as land acquisition, as it used

to be more common a decade ago (Bonnefond, Fournier, 2013). Costs and

negotiation processes are limited (as there is no acquisition), former

land uses can be maintained but they are controlled. However, it is also

important to point out some limits. Such projects often lead to an

increase of the flooded area locally, a decrease of the land value and

the necessity for their holders to organize discussions with landowners

and tenants about financial or material compensations. At last, it is

important to recall that such easement is permanent. It implies that any

future purchaser of the land must adhere to the easement.

Therefore, even though the over-flooding easement presents less

constraints than other legal instruments for the institutional holders,

in practice, it still implies discussion and negotiation between all

stakeholders involved locally and must be often combined with other

instruments. In the last section, we illustrate with a case study (on

the Oudon river basin) and describe how negotiation and arrangements

with local farmers have been necessary to successfully implement this

procedure.

4. A LEGAL INSTRUMENT CONFORTED BY LOCAL NEGOTIATIONS AND

ARRANGEMENTS: THE EXAMPLE OF THE OVER-FLOODING EASEMENTS ON THE OUDON

RIVER BASIN

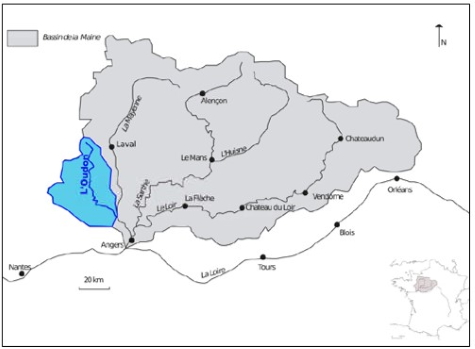

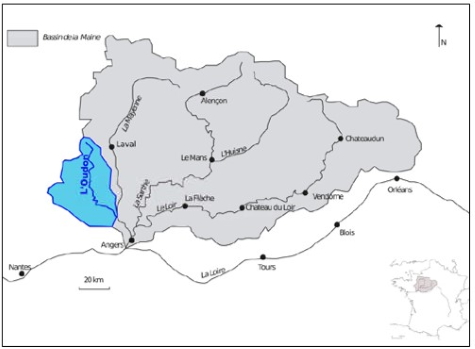

As we can see in Figure 2, the Oudon river basin is located in the

Western part of France (Maine-et-Loire/Mayenne Departments). The Oudon

river basin is mainly rural and dominated by farming activities.

Extensive grazing still remains in the bottom valleys but crop

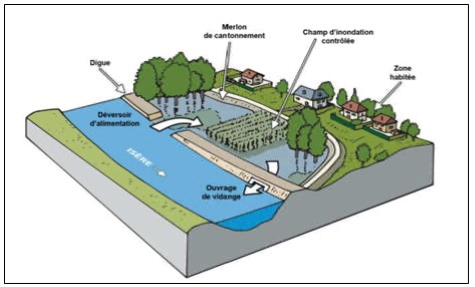

production is increasing. Figure 3 gives an overview of typical

landscape in the Oudon bottom valleys.

Figure 2: The Oudon river basin, in the

Western part of France

(credits: M. Bonnefond, 2018)

Figure 3: Meadows in the Oudon bottom

valleys/Segré en Anjou

(credits: A. Debray, 2018)

In France, local authorities and river syndicate on the Oudon river

basin were pilot in the implementation of this new type of public

utility easement. In the beginning of the 2000s, after several major

floods and major damages on hundreds of houses, they decided to create

flood storage areas; in their project, they quickly faced the land

tenure issue. Two options were considered: land acquisition or the

implementation of a new procedure, the over-flooding easement. As

explained during our interviews, local authorities decided to choose the

latter, in order to avoid/limit conflicts with farmers.

Several perimeters were settled in the southern part of the river

basin for the enforcement of the over-flooding easement first. Since

then, 12 perimeters have been delineated in total (the largest perimeter

is about 45 hectares). Locations were identified by the river syndicate

in cooperation with central government administrations and the Chambers

of Agriculture at local level (Maine-et-Loire and Mayenne Départements).

The river syndicate bought the parcels where hydraulic works had to be

built and the perimeters of the over-flooding easement delineated the

flood-prone areas.

Financial compensation, for both land owners and tenants, quickly

became a key issue. If the the river syndicate first considered the

parcels of little value, the Chambers of Agriculture battled to increase

compensations. In 2003, a first “agreement for compensation of land

owners and tenants” was signed, even before the enforcement of the

over-flooding easements. A 10% offset based on the land value was paid

to owners and financial compensations were also planned for tenants in

case of damages on crops, livestock and material goods (Debray et al.,

2019).

It is important to point out that local farmers also had the

opportunity to participate in the negotiation process. Since then, the

Oudon river syndicate forecasts about 20 000 euros every year to

compensate farmers.

The Oudon river syndicate had to face several difficulties and

oppositions, even though the Chambers of Agriculture were partners and

involved in the choice and design of this strategy; some perimeters were

abandoned because of local oppositions. The farmers, fearing the

economic and sanitary impacts of repeated floodings, as well as the

constraints on land farming, regularly contested the projects during

public meetings or meetings with the syndicate. If the Oudon river basin

was an early and pilot project, some authors describe similar issues on

other French river basins. On the Brévenne and Turdine river basin,

Riegel (2018) describes very finely how compensations have been

negotiated and calculated in agreement between the river syndicate

holding the project for the local authorities and professional

organizations defending the farmers’ interests. In particular, she

explains that indemnities have been calculated differently for each

farmer, taking into account the specific situation of each of them.

5. DISCUSSION

To conclude, the over-flooding public utility easement has

progressively become an important legal instrument for French local

authorities in the implementation of their mitigation projects dealing

with the flood hazard. In the years to come, the over-flooding of rural

and agricultural land may become more common in France to better protect

urban areas downstream. In this presentation, we pointed out the

advantages and limits of this procedure, which remains quite new and

still under experiment in many river basins. Local authorities tend to

avoid land acquisition and choose this procedure, which has permanent

legal consequences on land rights though. From our empirical

investigation, it appears that local negotiations constitute a key step

in its implementation and in the delimitation of perimeters. These steps

cannot be avoided by the institutional authorities in charge of such

projects. Unlike stated at the premises of the years 2010 by some

authors, landowners and tenants are far from being passive in its

proceedings and do not only bear the consequences of the easement

(Moliner-Dubost, 2013). They are consulted during the public inquiry and

most of all their involvement is crucial in the definition of the

perimeter and conditions of implementation (compensations, constraints

on land uses) of the easement. Empirical investigation shows that local

authorities often prefer to abandon projects if they do not reach an

agreement locally. Beyond the legal dimension of such procedure,

institutional holders must legitimate the flooding of rural land in the

benefits of cities and integrate the local socio-economic issues at

stake.

REFERENCES

Bonnefond, M., Fournier, M., Servain, S., Gralepois, M., 2017, « La

transaction foncière comme mode de régulation en matière de protection

contre les inondations. Analyse à partir de deux zones d’expansions de

crue : l’Île Saint Aubin (Angers) et le déversoir de la Bouillie (Blois)

», Revue Risques Urbains / Urban Risks, Vol 17- 2, ISTE Editions.

Bonnefond M., Fournier M., 2013, « Maîtrise foncière dans les espaces

ruraux. Un défi pour les projets de renaturation des cours d’eau »,

Economie rurale, n°334, p. 55-68.

Broussard, F., 2019, Préservation et gestion de la

multifonctionnalité dans les Zones d'Expansion de Crues : le cas du

bassin de la Maine, Mémoire de fin d’études, École Supérieure des

Géomètres et Topographes (Le Mans).

Debray, A., Fournier, M., Bonnefond, M., 2019, “Quels outils pour

concilier au mieux agriculture et gestion du risque d’inondation ? Mise

en oeuvre et effets de la servitude de sur-inondation sur les pratiques

agricoles dans les fonds de vallée”, 13èmes Journées de la Recherche en

Sciences Sociales, Société Française d’Economie Rurale, Bordeaux, 11-13

December 2019.

Fournier, M., 2019, “Flood Governance in France. From Hegemony to

Diversity in the French Flood‐Risk Management Actors' Network”, in

Lajeunesse, I., Larrue, C., Facing hydrometeorological extreme events: a

governance issue, Wiley.

Fournier, M., Larrue, C., Alexander, M., Hegger, D.L. T., Bakker,

M.H.N., Pettersson, M., Crabbé, A., Mees, H., Chorynski, A., 2016,

“Flood risk mitigation in Europe: how far away are we from the aspired

forms of adaptive governance?”, Ecology and Society, 21(4):49.

https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08991-210449

Hegger, D. L. T., Driessen, P.P.J., Wiering M., Van Rijswick

H.F.M.W., Kundzewicz Z.W., Matczak P., Crabbé A., Raadgever G.T., Bakker

M. H. N., Priest S. J., Larrue C., and Ek K, 2016, “Toward more flood

resilience: is a diversification of Flood Risk Management strategies the

way forward?” Ecology and Society, 21(4):52.

https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08854-210452

Larrue C., Bruzzone S., Lévy L., Gralepois M., Schellenberger T.,

Trémorin J-B., Fournier M., Manson C., Thuilier T., 2015, Analysing and

evaluating flood risk governance in France. From state policy to local

strategies, STAR-FLOOD (FP7/2007-2013).

Ministère de l’Agriculture et de l’Alimentation/Ministère de la

Transition Ecologique et Solidaire, 2018, Prise en compte de l’activité

agricole et des espaces naturels dans le cadre de la gestion des risques

d’inondation: guide destine aux acteurs locaux. Volet activité agricole

– version 2, 124p.

Moliner-Dubost, M., 2013, “Le destinataire des politiques

environnementales”, Revue Française de Droit Administratif, p. 505 et s.

Morris, J., Hess, T.M., Posthumus, H., Agriculture’s role in flood

adaptation and mitigation – policy issues and approaches, Sustainable

Management of Water Resources in Agriculture, OECD, Paris.

Morris, J., Beedell, J., Hess, T.M., 2016, “Mobilising flood risk

management services from rural land: principles and practice”, Journal

of Flood Risk Management, volume 9, p. 50-68.

Moss, T. Monstadt, J., 2008, Restoring Floodplains in Europe: Policy

contexts and project experiences, IWA Publishing.

Riegel, J., 2018, « Le dialogue territorial au risque de l’écologie?

Traces et effets d’une concertation entre aménagements hydrauliques et

restauration écologique », Participations, N° 20, 1, p. 173-198.

Struillou, J.-F., 2012, “Droit de preemption et prevention des

risques”, Actualité Juridique Droit Administratif, p. 1329 et s.

Warner, J., Edelenbos, J., Van Buuren, A., 2012, Making space for the

river: governance challenges. Making Space for the River. Governance

Experiences with Multifunctional River Flood Management in the US and

Europe, IWA Publishing.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Dr Marie Fournier is Assistant Professor in Urban and Land Planning

at the National Conservatory of Arts and Crafts (Conservatoire National

des Arts et Métiers- CNAM). In 2010, her PhD focused on public

participation in flood risk management policies. She is scientific

coordinator of the FARMaine research project (financed by the research

programme "On and For Regional Development" : www.psdr.fr). She is

involved in research projects which analyse the implementation of river

and wetland management policies in France. She has a specific focus on

local governance and the involvement of private stakeholders in public

policies. In her research, she is also interested in the design and

implementation of public instruments, local arrangements and their

consequences on land uses and land use rights.

Dr Adèle Debray holds a PhD in Urban and Land Planning (University of

Tours, 2015). She was post-doc researcher in the FARMaine research

project (www.psdr.fr). Her research

focuses on environmental policies and more specifically nature

conservation policies.

Dr Mathieu Bonnefond holds a PhD in Urban and Land Planning (University

of Tours, 2009). He is Assistant Professor in Land Planning at the

National Conservatory of Arts and Crafts (Conservatoire National des

Arts et Métiers - CNAM) and director of the european LTER (Long Term

Environmental Research) "Zone Atelier Loire". Most of his research is

related to the analysis of river management, environmental public

policies and land management.

CONTACTS

Marie Fournier

Laboratoire Géomatique et Foncier (EA4630), CNAM/HESAM

Ecole Supérieure des Géomètres et Topographes

1, boulevard Pythagore

72000 Le Mans

FRANCE

Tel. 0033 2 43 31 31 39

Web site: www.cnam.fr